Written December 22, 2007, Hotel Diganga, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

More catchup–

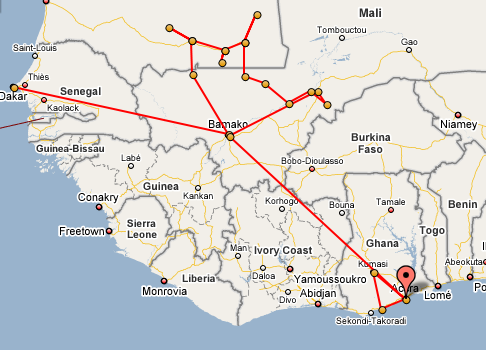

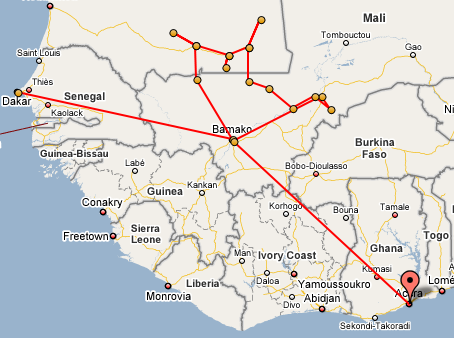

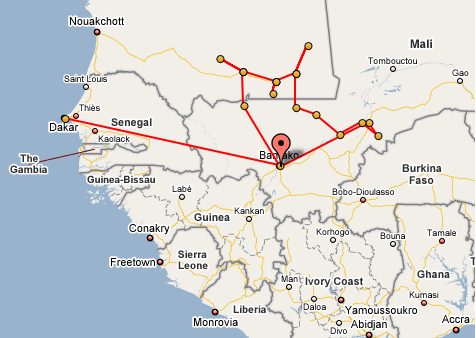

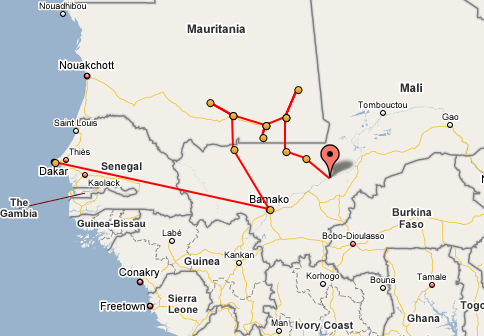

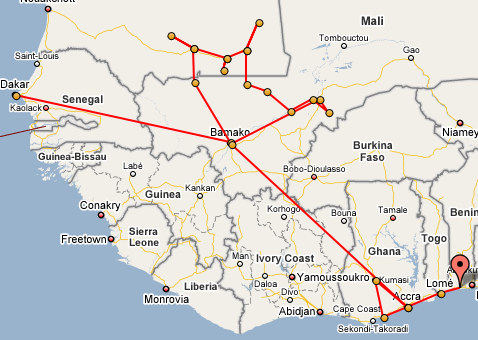

Then, I went to the main market in Lomé to change my Ghana cedis into CFA used in Togo, Benin, and other francophone West African countries. I managed a not-so-great rate, then tried getting a taxi back to the hotel, which didn’t happen until after I got hot and tired wandering through the market. The guys at the hotel were nice to me and helped me get my bags into a taxi and on my way to the Togo-Benin border.

At each of these borders, it amazed me how the immigration officials were taking bribes to let people pass through despite minor infractions of law or policy. So many of them tried to get me to give money, but I refused. Since I carry a US passport and pay a big visa fee already, I can get away with it.

At least at this border, it was the same shared taxi who waited for us on the Benin side who had dropped us off on the Togo side. I got the ride to Ouidah, then got overcharged for a ride to the Jardin Brasilien, a delightful hotel on the beachfront.

Written December 22, 2007, Hotel Diganga, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

More catchup–

At the Jardin Brasilien, they had a swimming pool filed with sea water.

What a great place to relax from the stress of travel, with the sound of the pounding surf soothing my sleep. I showered in the room before heading over to the pool with the lifeguard came running over before I jumped in to let me know I had to shower. I explained I had already showered, but he was concerned about the sand on my feet getting into the pool. I washed off again and enjoyed a delightful swim just as an elderly fellow was getting out of the pool to go for a walk with a woman I came to find out is his wife. On the way out of the pool, I met a French fellow named Jacques and we agreed to eat dinner together that evening at 8pm. I was so exhausted from travel and a big of digestive trouble that I napped for a few hours before rousing myself for dinner.

Jacques, an older guy from the Mediterranean coast of France, was on a fascinating quest. He served his French military service 40 years ago in Benin, specifically in Parakou in the central to northern part of Benin. While serving, he went to a village where he took some pictures. One guy got upset at him for taking one of the pictures and, after resolving the conflict, Jacques promised to retunr one day to give him a copy of the picture. Jacques had returned to honor his promise after 40 years, but unfortunately the fellow had already died, so Jacques gave the pictures to his family. Jacques searched in another village nearby for a baby who had appeared in one of the old photos. When he found her, the bonded instantly. Jacques ended up asking her what he could do to help her life in the village. She answered that she was trying to set up a nice shop for food and other items, so Jacques financed the operation. He stayed for a couple of weeks, living on pounded yam (igname) every day til the place was set up. I encountered him taking a break to relax from his travel to the village. He had met Isaac (?), the chief lifeguard at the hotel, who asked Jacques if he could help him with some fishing equipment. Jacques agreed. He spent a few days getting the fishing operation set up, impressed by Isaac’s determination, persistence, and courage, for example swimming for nearly an hour after dusk to put the nets out from the shore. The first night they caught nothing, but after placing live instead of dead bait on the hooks, they caught a few man-of-ray’s, including one that delivered two babies on capture. Apparently, people do eat the rays, so Isaac was on his way to town to sell the fish, except for one Jacques and some of the other hotel guests hoped to eat themselves.

My first morning in Ouidah, I met Henri and his girlfriend Natalie who were visiting, biking around, and on vacation from their jobs in Filingué, a few hours drive outside Niamey in Niger. I talked mostly with him, since she wasn’t feeling well with something that sounded exactly like what I had. I found him quite attractive. They ended up inviting me to come visit them after New Year’s in the village, and perhaps I will. He works with cattle breeding and she works in the local radio station.

Off I went to town, on a motorcycle taxi (called taxi-moto or zemi-john) after Jacques’ encouragement to transcend my fears about that mode of transport. On the sandy road, I actually felt safe riding along at a reasonable speed with the sand to cushion any fall. It was only on the cobbled and paved roads that I got anxious.

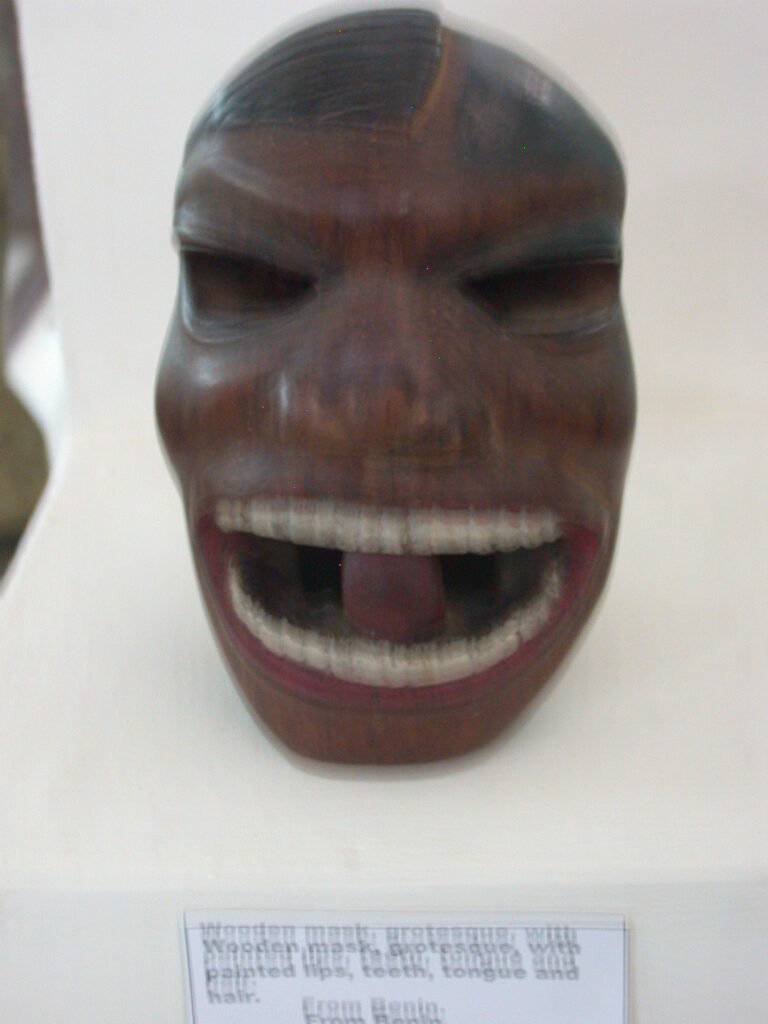

I stopped by the residence of the main chief of Ouidah, Daagbo (see entry of December 11). He asked me to return later that day to snap photos and see the ceremony for the initiates who spent nine months in preparation. Before returning for the ceremony, I visited the local history museum, the Musée d’Histoire de Ouidah, where I met Olivier Coyotte, a Belgian playwright of Turkish origin, and Simon Kind, an attractive Québecois fellow.

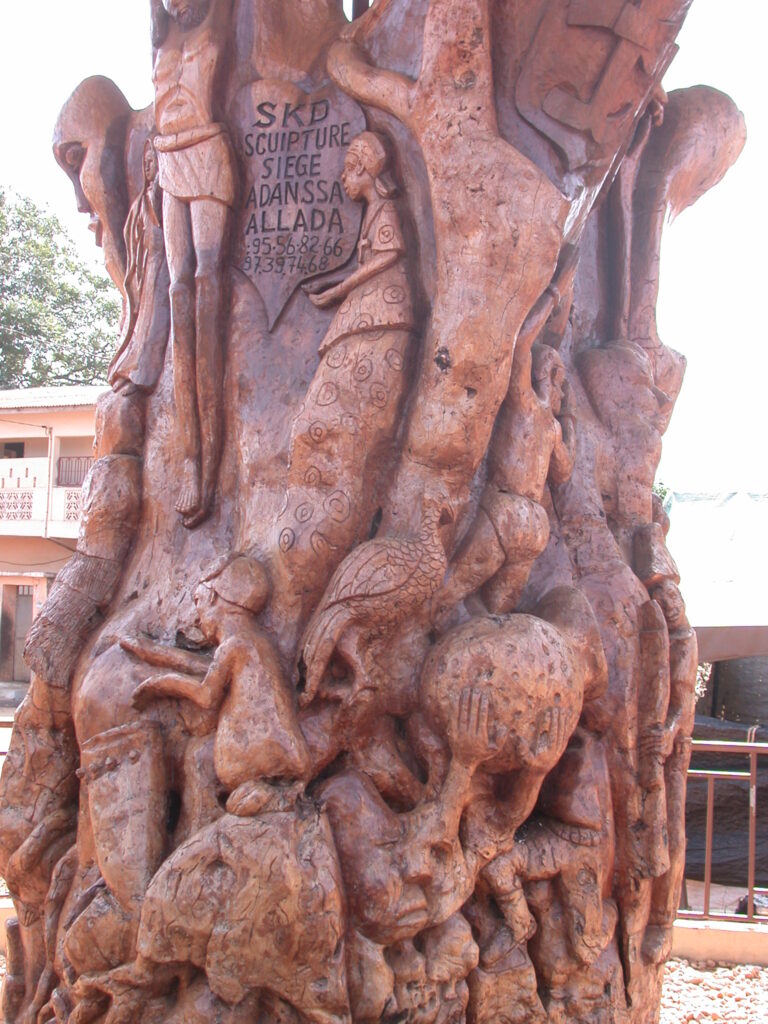

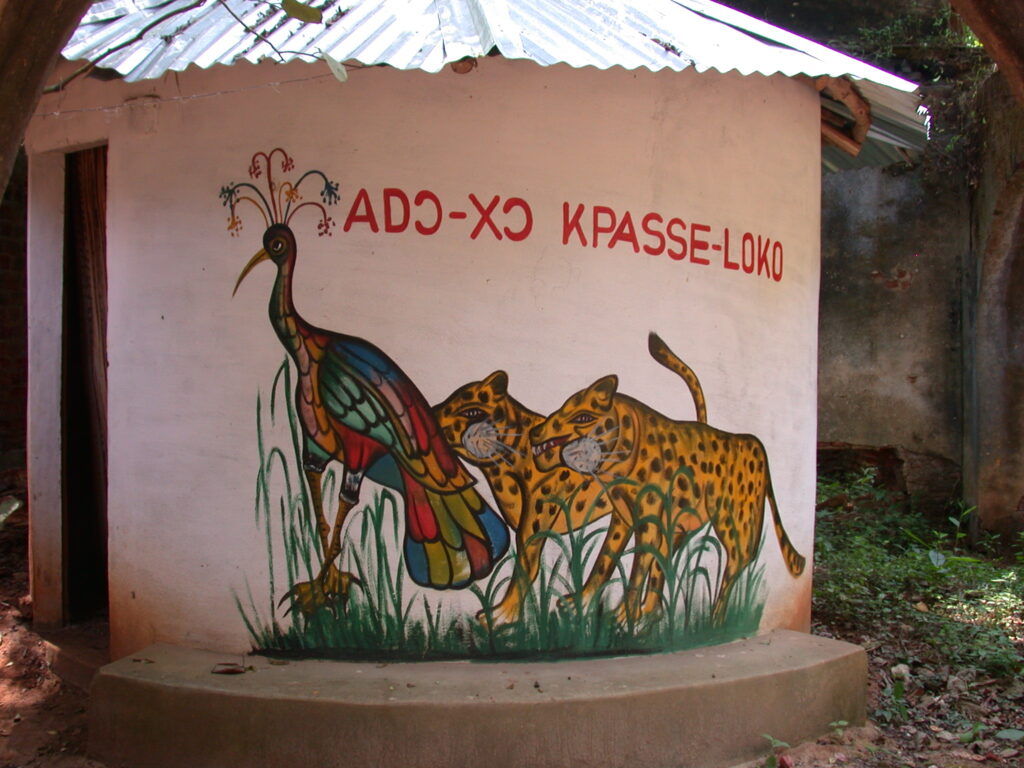

I walked to Kpassezoume, or the Kpasse Sacred Forest, which had wonderful sculptures of the various Yoruba divinities, as well as a rare iroko tree said to be the tree King Kpassé turned himself into while fleeing enemies. One finds in the forest the works of contemporary sculptors Cyprien Tokoudagba, Theodore and Calixte Dakpogan, and Simonet Biokou. According to this quote of Dana Rush from an African Arts article of December 22, 2001:

Sometime between 1530 and 1580, Kpasse became the second king of Savi (located nine kilometers north of Ouidah) and founder of Ouidah. When he learned that two jealous enemies were plotting his demise, he alerted his two sons, telling them that although he would never die, he would disappear one day. If it should happen that he did not come out of his room before sunset, his sons were not to open the door but understand that he was already gone. After nine days they would see a specific sign from their father which, once understood, would protect them and their families for generations to come. One day these events did come to pass. Today the sign is still a secret associated with the Kpasse vodun, known only to the direct descendants of the king.

Soon after King Kpasse disappeared, his family living in Savi saw a bird they had never seen before. It led them to the Sacred Forest in Ouidah. Upon entering the sacred grounds of the forest, the bird turned into two growling panthers (male and female). The family was frightened until they heard the soothing voice of the king. He gave them an important message: if at any time they were having problems, they could come to the forest and pray to a specific iroko tree that houses his spirit. The tree was then just a little sprout next to a sacred clay pot. Today, behind the ruins of the old French administrative house in the Sacred Forest, abandoned because the spirits were “too strong” for the French, one finds active shrines, including a clay pot, next to the tree in which Kpasse’s spirit resides (interview with the current King Kpasse, July 19, 1995).

I made a wish by touching the iroko tree said to be King Kpasse and leaving an offering (last picture above).

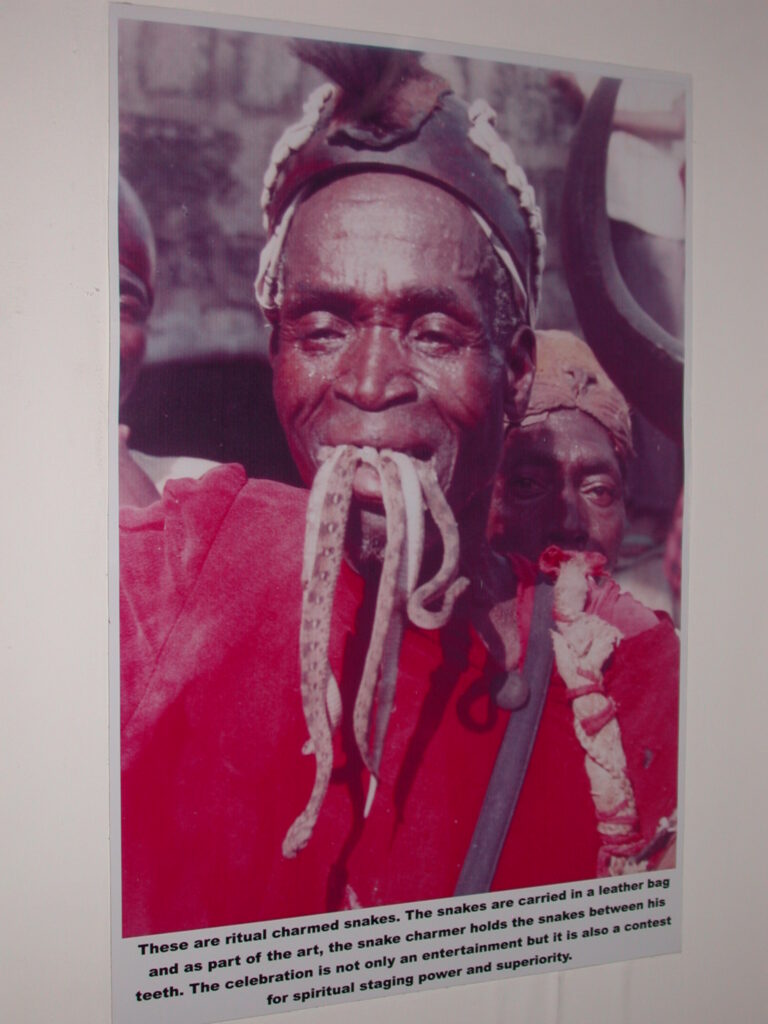

After leaving the sacred forest, I rode a zemi to the python temple where they tried to gouge me for cash to take photos which I fortunately refused because the temple was interesting, but rather small. They had a roundhouse full of pythons who stay inside during the day then go out at night to feed on rodents. Residents of Ouidah respect the pythons and return them to the temple if found on the streets. Every 9(?) years, a ceremony takes place at the temple, the details of which the guide would not really elaborate, somewhat infuriatingly repeating the same stock response over and over while also asking if I had any more questions. You can read more and see photographs of this python temple at Xeni Jardin’s blog.

After the pythons, I walked toward Daagbo’s residence. On the way, I chatted with a few guys hanging out in a telecom shop. I took a picture of this sculpture carved from an old tree to represent the history of Ouidah.