Written on November 27, 2007, Sevaré Motel, Sevaré near Mopti, Mali

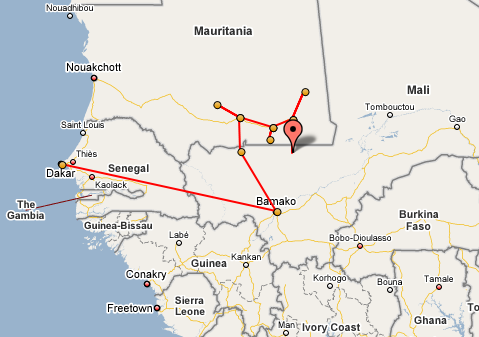

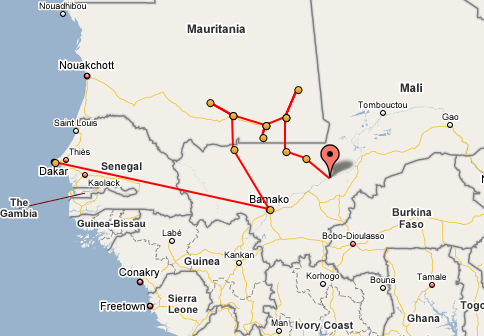

The rest of the trip from Mauritania down to Djenné in Mali on November 22 and 23 was quite difficult. The first stage from Nema to Adel Bagrou wasn’t a very good road, although not as bad as the road from Nema to Oualata. At Adel Bagrou, I switched to another vehicle and we crossed the border at night. I was careful to make sure the Mauritanian border control stamped my passport on departure and the Malian border control stamped it on my second entry to Mali.

Arriving at night at Nara, some guys sitting near the garage got a local guy who works at the radio station in town to come by and show me a room he rents out. The room was filthy and had no running water. I took it anyway because I knew I’d be leaving the next morning. I went back to the street to have a kind of scrambled eggs made on a little gas stove while I sat drinking an apple juice on a wooden bench near the marketplace.

After a rough night and a tough morning, I had a great experience here in Nara. The rough night was because I stayed in a filthy room with no running water and didn’t adjust my mosquito net properly until after the muezzin calls in the morning. The tough morning was after I checked out of the hotel thinking I would be able to get on a truck for Selegou at 9:30am and make it to Niono by this evening and Djenné by tomorrow. Now, it looks like the truck won’t leave until 2:30pm or later. The truck driver named Lasana has a father, a retired teacher, who took pity on me and invited me to the family compound where about 40 people live. Such wonderful hospitality was a great antidote to the travails of travel. I even learned that they are Sonninké people descended from those of the Wagadu empire. Lasana has a twin brother named Fusiné. Here are some more details…

I broke out the mosquito net to crash out early. I didn’t get it adjusted properly until early the next morning. I soon remembered that it doesn’t do much good unless the net is always a bit away from one’s body; otherwise, the damn mosquitoes can sting you through the net! Later that morning, I tried for a vehicle all the way to Niono, but could only find one that would go to Sokolo. I asked when the vehicle would leave and the head of the driver’s syndicate told me it would leave in about an hour and a half at 9:30am. So, I told him I’d go back and bring my bags over. On the way back to the hotel, I tried to change my Mauritanian ougiyas at a reasonable rate with several different moneychangers. The best rate I could find was 16,667 CFA for my 9,000 ougiyas, when the amount should have been around 18,000 CFA. O well. Next, I bought some drinks, then checked out of the hotel and dragged my bags over to the first vehicle destined for Sokolo. I waited around for quite awhile, buying a coffee and a couple loaves of bread, then found out that the vehicle wouldn’t leave until at least 2:30pm. Fortunately, the father of one of the syndicate driver’s saw me chatting with a former colleague of his, both of them retired teachers, and decided to invite me back to his place for lunch. His son the driver brought me over. I had to explain before going about my vegetarianism, but the family seemed quite accommodating about it. I enjoyed visiting the family compound where about 40 people live. I got to eat couscous with milk and sugar, instead of the couscous with meat and sauce that everyone else ate. We talked a bit and he mentioned that the family is Sonninké and that they are descendants of the residents of the empire of Wagadu. After lunch, the son walked me back to the family’s rice and flour shop to wait until the vehicle would be ready. We drank tea and chatted a lot.

Finally, the truck was ready to go around 4:30pm or later, and we left. I’m glad I got to visit the family.

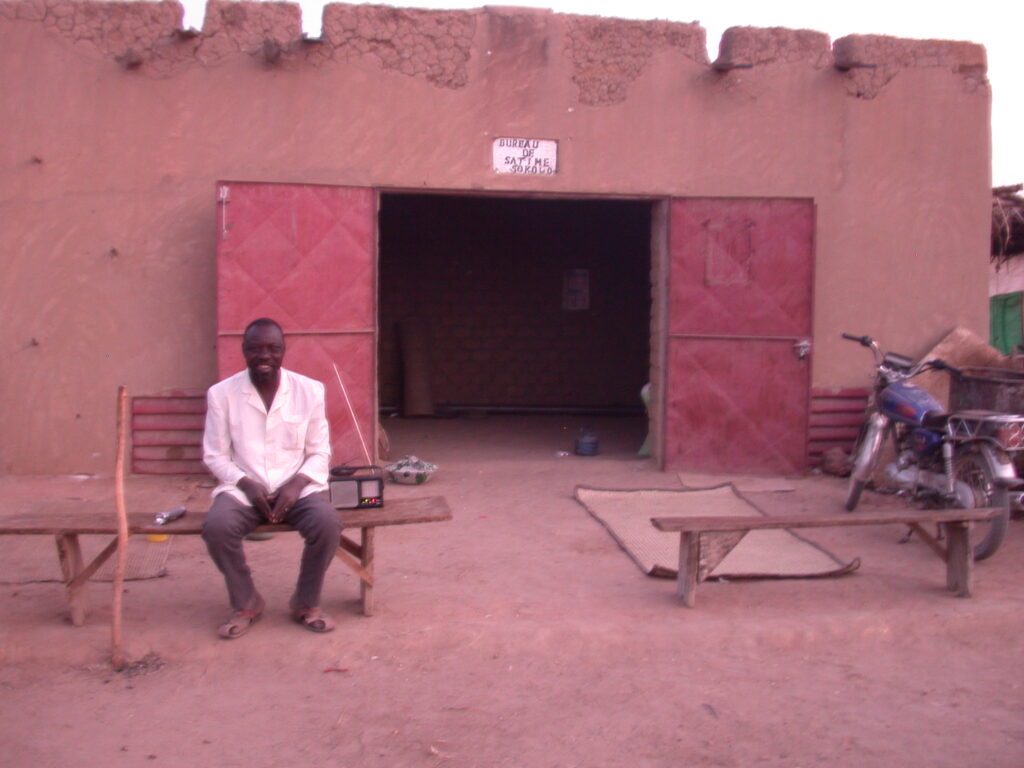

The unfortunate result however was that I got stuck overnighting at the syndicat in Sokolo, a mostly outdoor place right next to the dirt yard where the vehicles gather to take on or drop off passengers (see last pic above). In the syndicat, people were sleeping on mats. At first I was a bit afraid, but there was a guardian (shown in the pic) there who kept and eye out for everyone and their stuff.

Early the next morning, I got on a vehicle to Niono where I ate lunch and bought a bottle of mineral water.

Then, I headed on in another vehicle to Massina.

At Massina, I encountered the River Niger in full force, including fish and large boats in the small but bustling river port.

I paid 2000 CFA to cross the Niger River in a pirogue that was taking on water. I’m sure I would have paid much less had I waited a few minutes more to cross on the usual passenger boat, constructed by strapped two pirogues together.

When I reached the sand beach on the other side of the river, there was no public transport in site. A kind truck driver offered me a ride to the villages of Souléi then Say.

In Say, guys sitting by the road greeted me with tasty watermelon. Walking over to the other side of town with a local guy’s help for my large bag, I chatted with the town’s mayor for quite awhile while reclining in wood slat chairs and drinking tea. A car came by around 9pm and took me on to a small town that was called Matabou (I think).When I arrived in that town, the vehicle I arrived in had problems and the only other vehicle that wasn’t a motorcycle was sitting unoccupied right next to it. So, I almost decided to crash for night, but I remembered I had told Chicago, my prospective guide, that we should go that day. Finally, with the assistance of a guy who worked the telephone call box and a clothing stylist in town, I managed to reach Chicago on the phone and he negotiated to send a taxi to me, also rough going. He showed up in the taxi, which ended up costing me a whopping $80+. I checked in to the Campement de Djenné hotel around 1:30am and didn’t get to sleep until after I completed a shower around 3am. Chicago and I had agreed to meet each other at 10:30am.

I actually managed to wake up on time despite incredible fatigue from the journey. Over breakfast, I realized I had done something stupid. Chicago had quoted me a price by email for a trip to the Dogon country. I mistakenly thought he had quoted around US$50 per day when it was actually US$500 per day. That explained why he showed up in Djenné three days before our scheduled departure date. Over breakfast at Ali Babu’s place nearby, I told him that I had made a big mistake and apologized. I said there was no way I could afford to pay anything like what he was seeking and offered to compensate him for his trip from Timbuktu instead. He tried proposing some other pricing which was still way too high for me. Finally, he asked what I could afford. I told him around US$50 per day. He obviously really wanted to make the trip work, and of course had offered a highly inflated initial price, so we actually managed to come to an agreement that worked for both of us.

That day, I saw the old mosque at Jenné and a tour of that old city.

Next, we went to the museum at the even older town of Jenne-Jeno.

I managed a visit to the site of the archaeological dig that McIntosh had directed at Jenne-Jano as well. Chicago was kind enough to return on foot to arrange our transport on to the Dogon country while I got a ride with a museum attendant and archaeologist to the ancient city on the back of his motorcycle. As a student, he had participated in the excavation of the site and planned to participate again when McIntosh returns next year. The site seemed possibly as large as Koumbi Salah and had lots of pottery shards and iron ore castoffs.

In one spot, a stream had eroded the earth surrounding a vase buried under the sand, so you could see one whole side of the vase while it was still fully buried on the other side (picture just above). The ceramic vases were apparently used for a variety of purposes, such as for food storage. When used to hide treasure, vases were layered inside one another. Funerary vases (including those in the last few pictures from the museum above) had a hole intentionally poked in the bottom of the vase so it was clear the vase wasn’t used for a ‘practical’ purpose. I was struck by the thought of the discovery at Jenne of the seemingly Indian-style statue I had seen at the Musée Nationale du Mali in Bamako.

As soon as the museum curator got me back onto the main road, Chicago, the taxi driver, and another passenger picked me up in the taxi and off we went to Dogon country. The first stop along the way was at a Niger River crossing. Chicago didn’t stop three teenage women from surrounding me up against the taxi to sell their wares. Finally, I got it across to them I wasn’t interested, so I got to wander around the riverside a bit while waiting for the car ferry to show up from the other side of the river.

We spotted a young hippo near the other side of the river, and when we finally made it across, the hippo lifted himself out of the water and turned around so we could see him really well. Apparently it’s not a common site because the local people were quite excited by it as well.

The taxi took us to the garage at Bandiagara where we shifted over almost immediately to a vehicle that was already full of people, including four Mali Peace Corps volunteers. So, even though two of the female Peace Corps volunteers were squished very tightly along with Chicago and myself into a back seat meant for two passengers, we made interesting conversation along the way. At Bandiagara, Chicago and I shifted into a taxi to get the rest of the way to Dogon country. Someone, perhaps a friend of Chicago’s offered me to buy some cola for the elders at the first Dogon village, but I though he meant Coca-Cola and decided I didn’t want to offer that as a gift. I later found out he meant cola nuts, which the elder Dogons love to chew. I had trouble purchasing bottles of water from the same guy because he tried to charge me a higher price for cold water than tepid water. I got annoyed and gave him the money telling him to bring me the hottest bottles of water he had. He ended up bringing some fairly cool ones for the lower price. It was lucky I got those water bottles at 500 CFA because the water bottles once at the Dogon villages went up to 1000 CFA.