Written on December 25, 2007, Fajol Castle Hotel, Abeokuta, Nigeria

More catchup–

Abomey has an amazingly rich cultural heritage with a lot of history based on the royal kingdom known as Dahomey or Danhomê. I set out on foot from the hotel on a tour described in my guidebook.

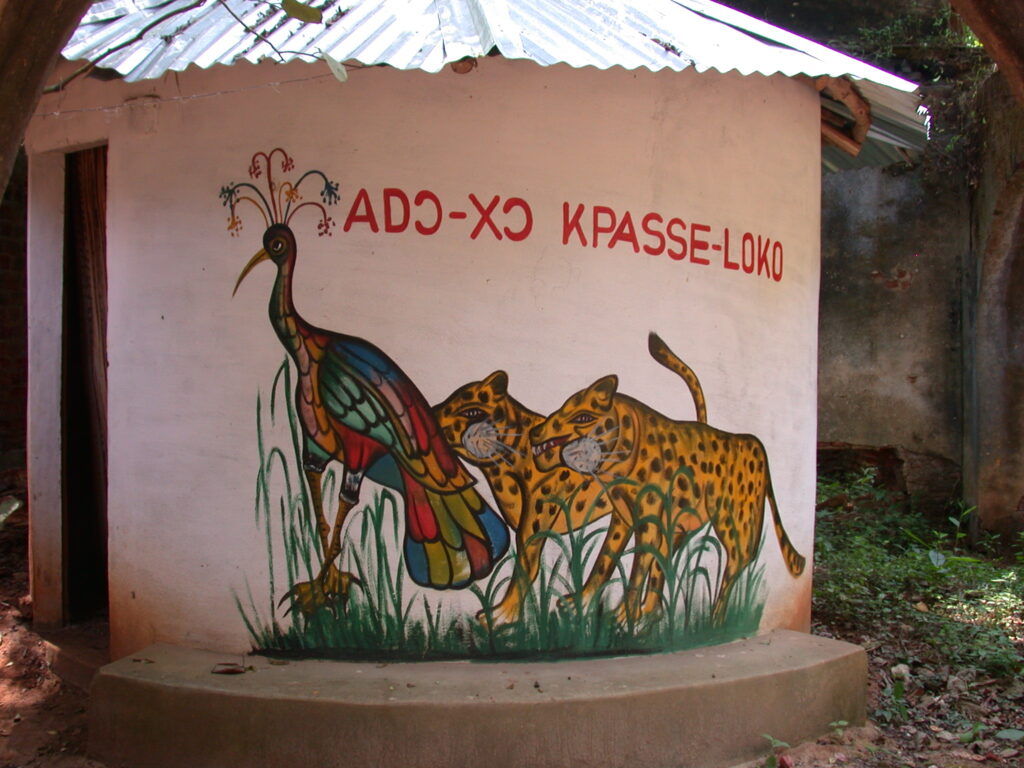

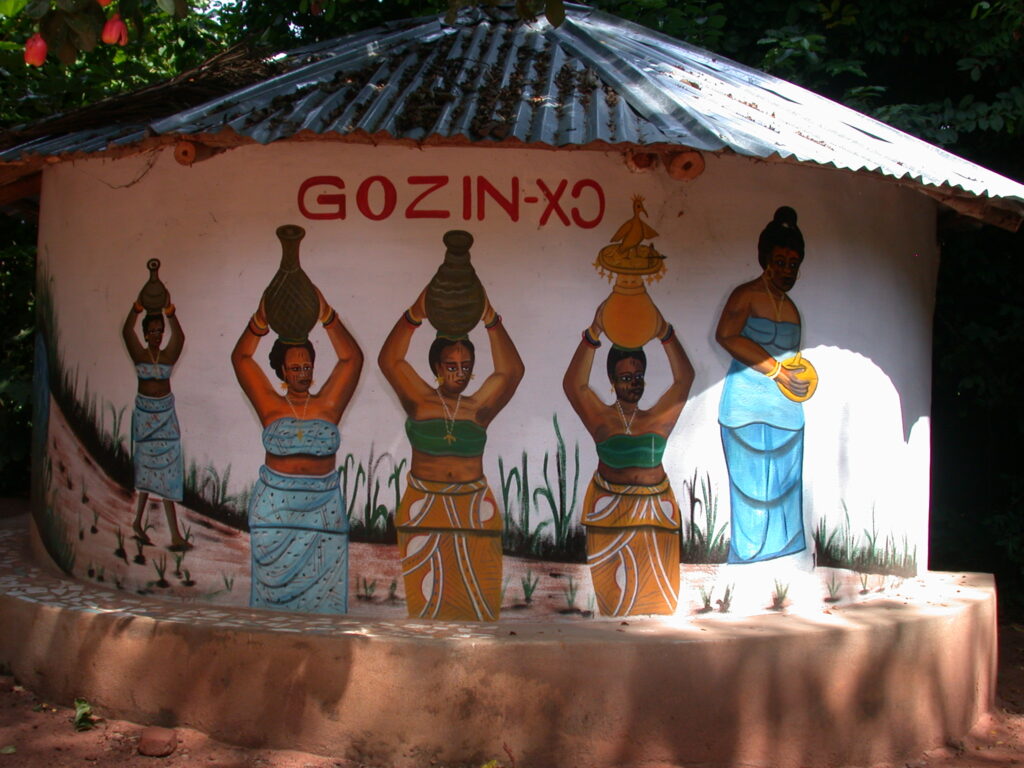

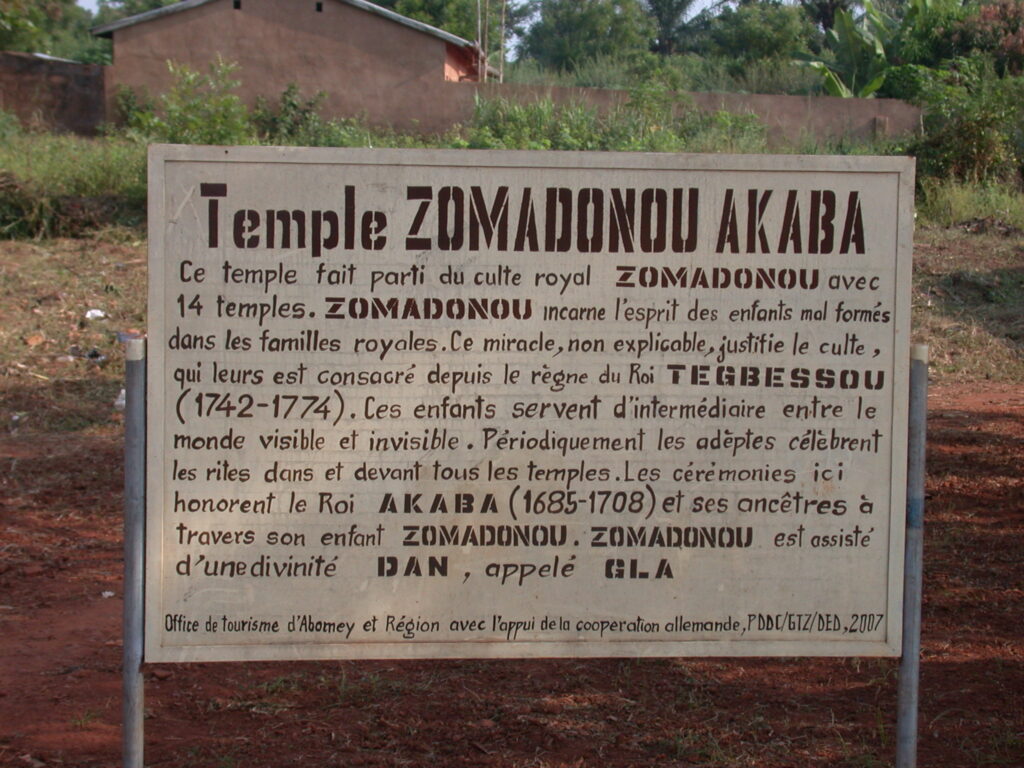

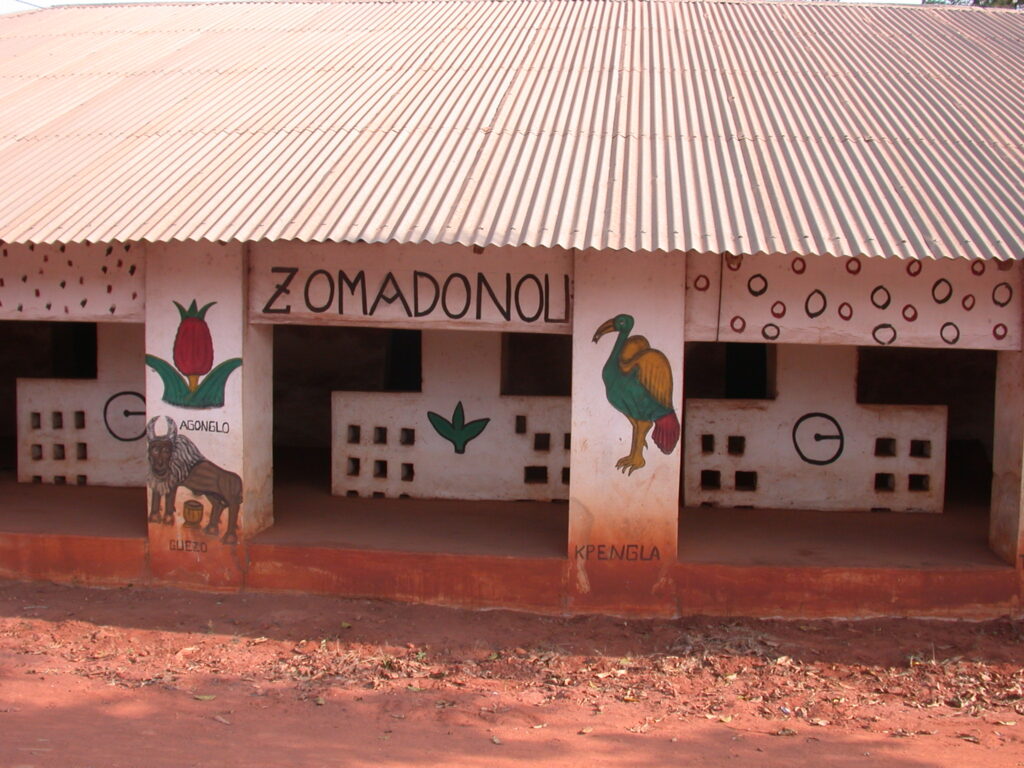

The first stop was to be the ancient city moat, but I ran into other sites along the way. After a ruined palace wall, I came across the Zomadonou Akaba Temple and its sign which read as follows in English translation of the French original:

The Zomadonou Akaba Temple

This temple is part of the royal cult of Zomadonou with 14 temples. Zomadonou incarnates the spirit of malformed children in the royal family. This inexplicable miracle justifies the consecration of the cult during the reign of King Tegbessou (1742-1774). These children serve as intermediaries between the visible and invisible world. Periodically the adepts celebrate rites in and in front of all the temples. The ceremonies here honor King Akaba (1685-1708) and his ancestors through his child Zomadonou. Zomadonou is assisted by a Dan divinity named Gla.

Heads of the royalty each have a symbol associated with their reign, such as these for Agonglo, Guezo, and Kpengla aka Kpingla (picture below).

I came across a sign depicting one modern hair salon’s idea of the standard of feminine beauty in this region.

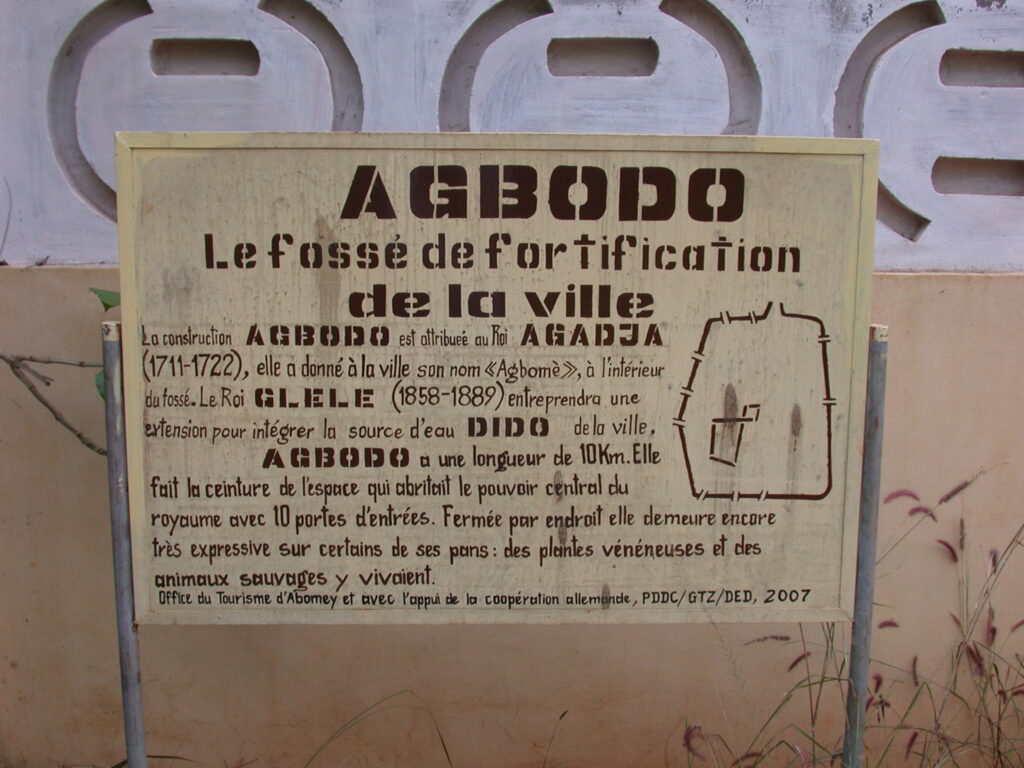

There are around 41 palaces in various states of preservation, use, or decay around the town. I tried to keep track of them all as I went. Amazingly, some people living right next to the sites have no knowledge of them or simply don’t understand or want to understand or think they can possibly understand me because I’m a strange foreigner. On the way to the moat, I asked people for directions along the way. Finally, when I was about 20 yards from the place, someone figured out what I was talking about. I saw the moat, locally known as Agbodo, and and took pictures of it.

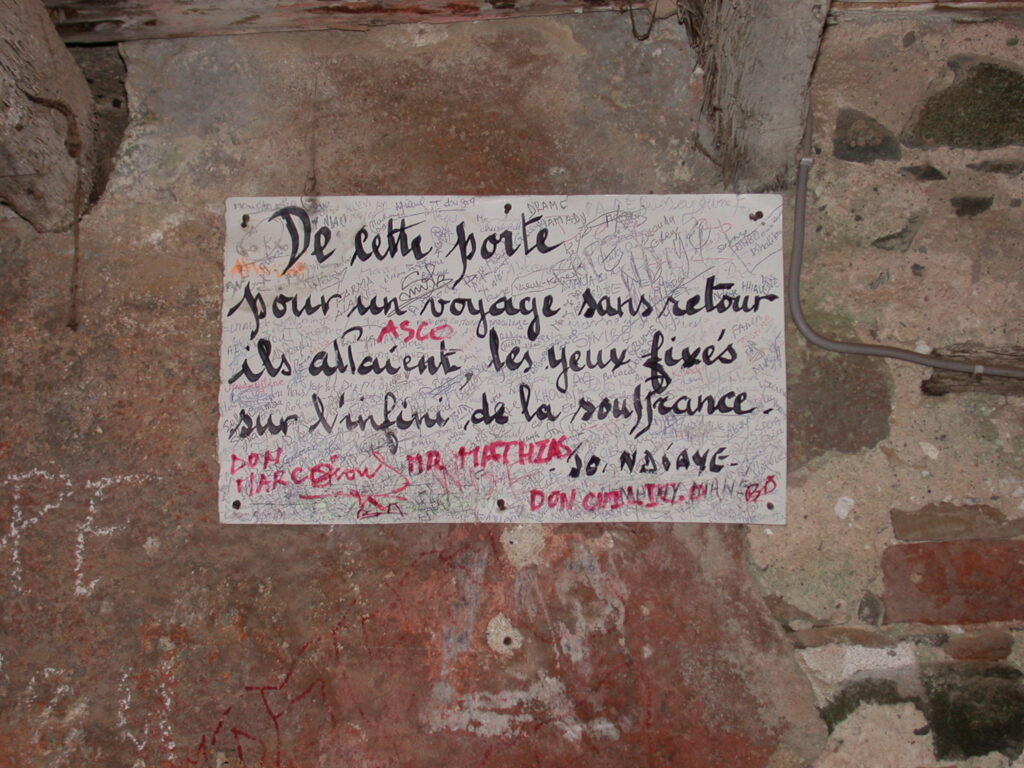

The English translation of the French sign follows:

Agbodo: The Moat of the City

The Agbodo construction is attributed to King Agadja (1711-1722) and gave the city its name of “Agbomè,” inside the moat. King Glele (1858-1889) will undertake [sic] an extension to include the Dido water source of the city. Agbodo is 10km long. It surrounds the space which sheltered the central capacity of the kingdom with 10 entrance doors. Closed in places, it still remains very expressive of certain of its sides: poisonous plants and savage animals lived there.

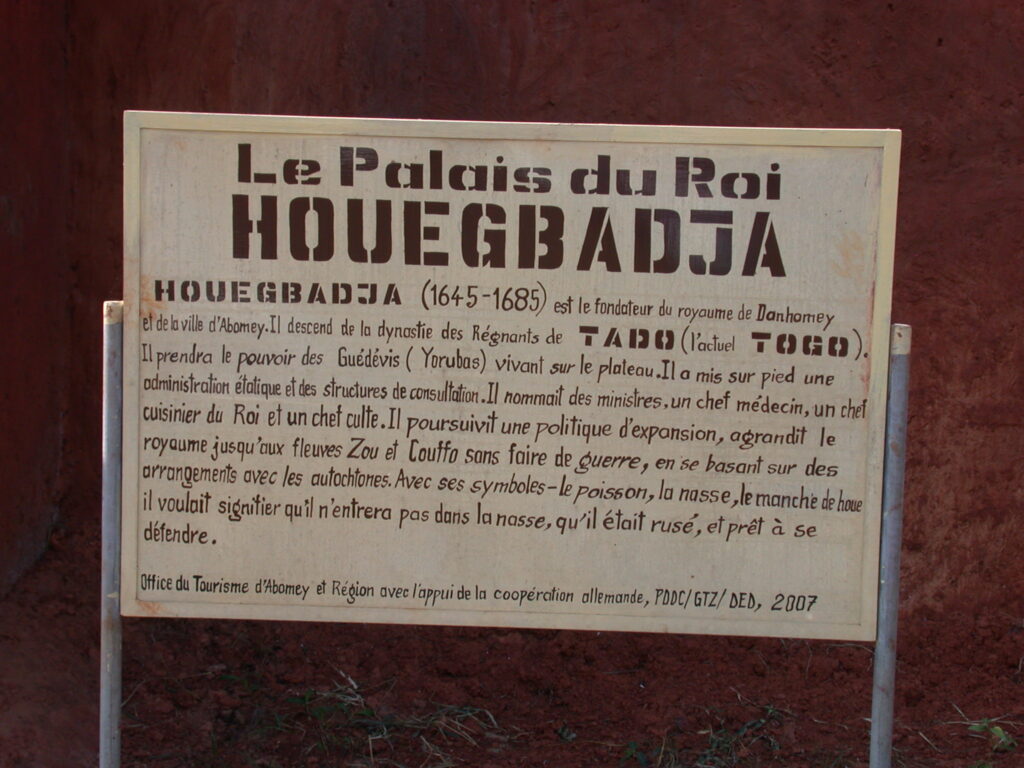

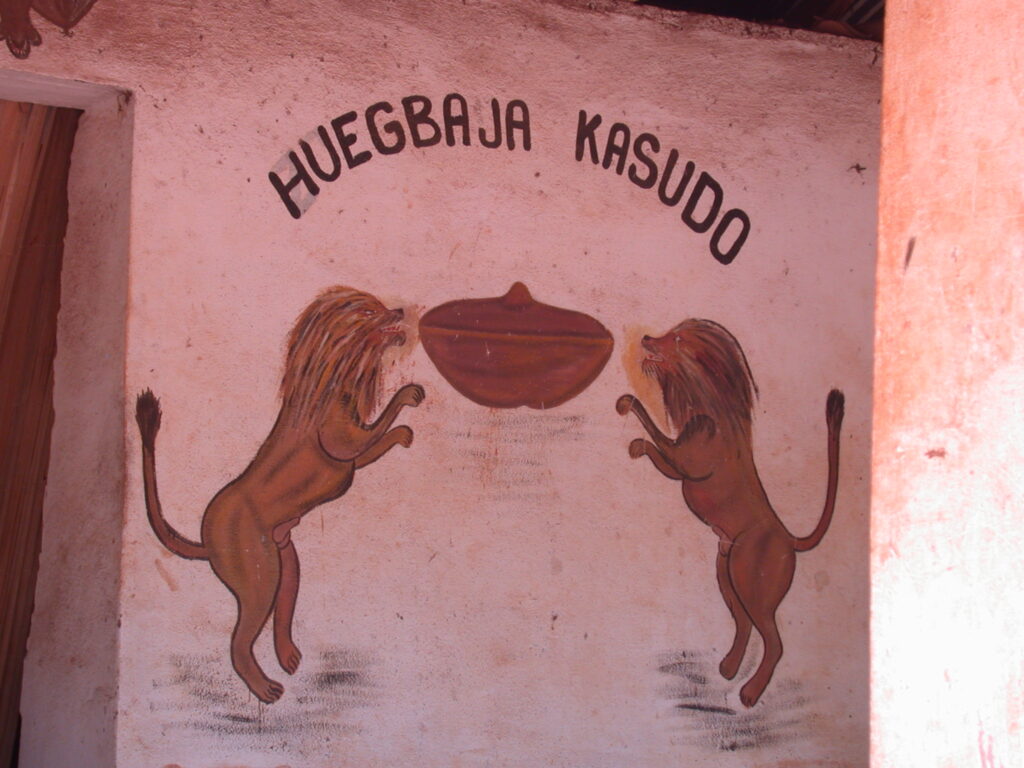

Then I walked onward. It was a long walk, but I’ve found that walking is the best way to really see the sites and get to know the people and the surroundings as they are today. For example, I stopped to look at a flowering tree and a fellow piped in to let me know that he makes an infusion from its leaves to treat malaria. I also saw a traditional oven used to bake bread. I also saw a house that identified Houegbadja, the third king of Dahomey.

Next came King Houegbadja’s palace for which the English translation of the French sign is:

The Palace of King Houegbadja

Houegbadja (1645-1685) is the founder of the kingdom of Danhomey and the city of Abomey. He comes from the dynasty of the rulers of Tado (present-day Togo). He will seize [sic] the power of the Guédévis (Yorubas) living on the plateau. He set up an official administration and consultation structures. He named some ministers, a medicine chief, a chief chef of the king, and a cult chief. He pursued expansionist politics, extending the kingdom to the Zou and Couffo rivers without making war, based on negotiations with the natives. With his symbols — the fish, the bow net, and the hoe handle — he wanted to signify that he will never enter into a net, that he was clever, and ready to defend himself.

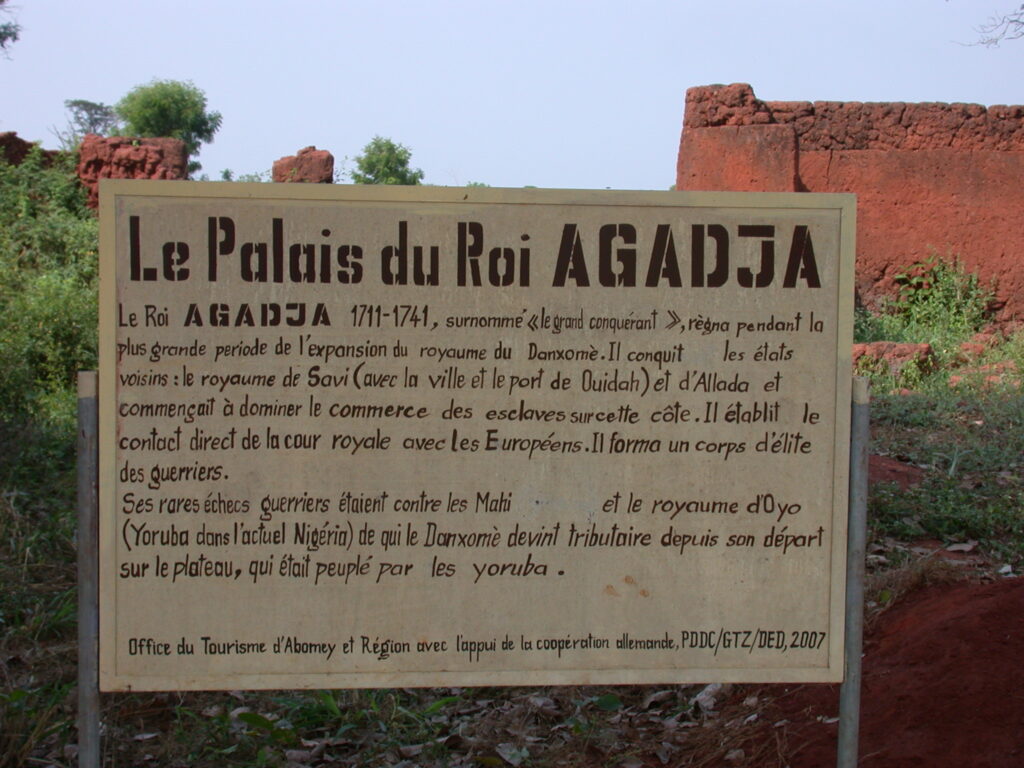

Next I visited the palace of King Agadja. My English translation of the French sign follows:

The Palace of King Agadja

King Agadja (1711-1741), called “the great conqueror,” reigned during the biggest period of expansion of the Danxomè kingdom. He conquered neighboring states: the kingdom of Savi (with the city and port of Ouidah) and Allada and started to dominate slave commerce on this coast. He established direct contact from the royal court to the Europeans. He formed an elite corps of warriors. Its rare warlike failures were against the Mahi and the Oyo kingdom (Yoruba in present-day Nigeria) of which the Danxomè gave tribute since its departure on the plateau, which was populated by the Yoruba.

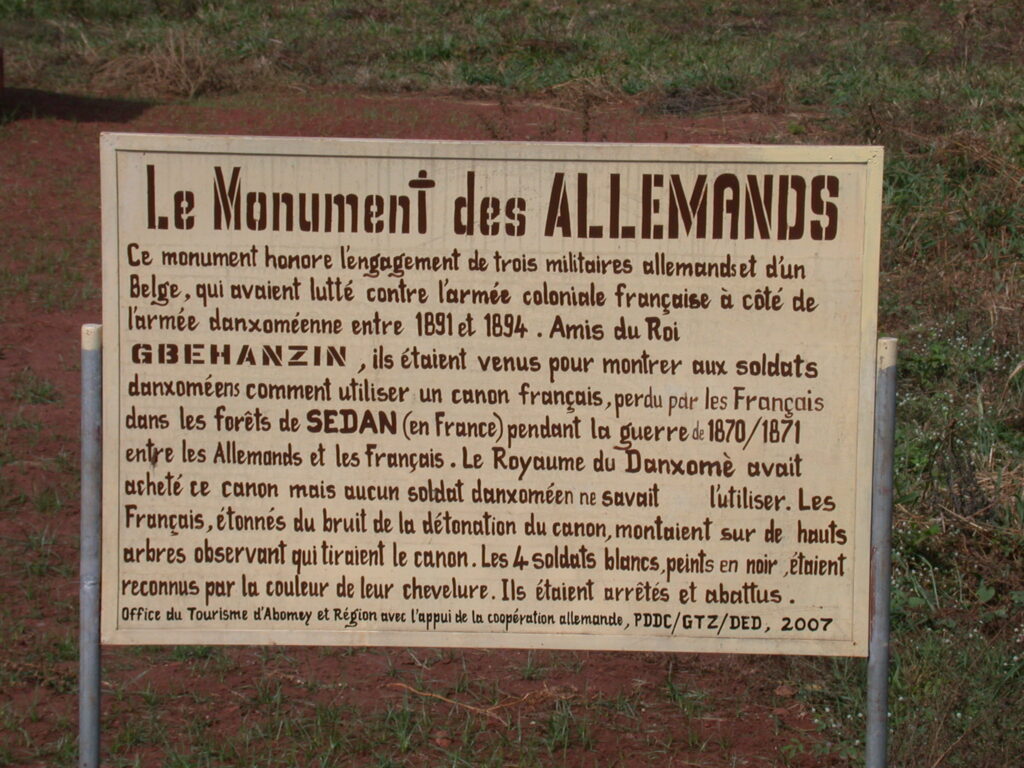

Next came the monument to the three Germans. Here’s my translation of the French sign:

The Monument to the Germans

This monument honors the engagement of three German soldiers and of a Belgian who fought against the colonial French army side by side with the Danxomè army between 1891 and 1894. Friends of King Gbehanzin, they came to show the Danxomè soldiers how to use a French cannon, lost by the French in the forests of Sedan (in France) during the war of 1870/1871 between the Germans and the French. The Kingdom of Danxomè bought this cannon but no Danxomè soldier knew how to use it. The French, astonished by the sound of the cannon’s detonation, climbed into tall trees to observe who was shooting the cannon. The 4 white soldiers, painted black, were recognized by the color of their hair. They were arrested and executed.

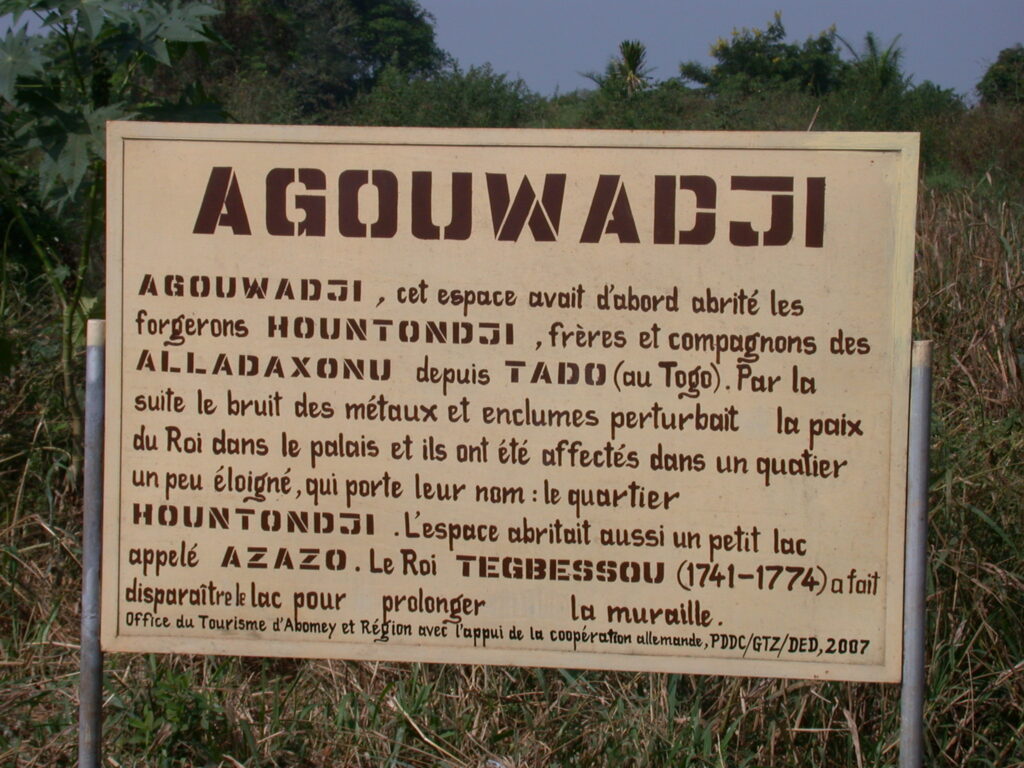

The Agouwadji ruins once sheltered the Houtondji blacksmiths as described in my translation of the French sign there:

Agouwadji, this space once sheltered the Houtondji blacksmiths, brothers and companions of the Alladaxonu since Tado (in Togo). Then the noise of metal and anvils disturbed the peace of the King in the palace and they were moved to another district a bit further away, that bears their name: le Houtondji district. The space also sheltered a little lake named Azazo. King Tegbessou (1741-1774) made the lake disappear to extend the wall.

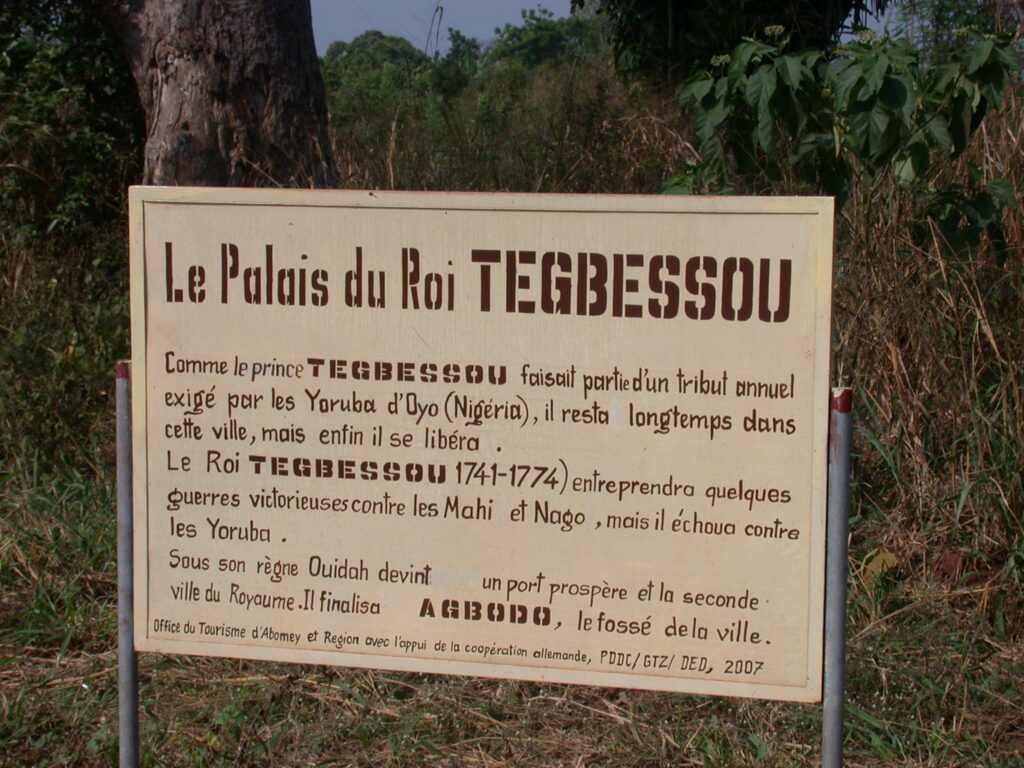

The palace of King Tegbessou also has a French sign for which I present here the English translation:

The Palace of King Tegbessou

Since the prince Tegbessou was part of an annual tribute demanded by the Yoruba of Oyo (Nigeria), he stayed for a long time in that city, but finally he freed himself.

King Tegbessou (1741-1774) undertook some victorious wars against the Mahi and Nago, but he failed against the Yoruba.

During his reign Ouidah became a prosperous port and the second city of the kingdom. He finalized Agbodo, the moat of the city.

Here is my translation of the French sign that describes the Feliadji entrance:

The Feliadji Entrance

The Feliadji entrance was opened by the King Tegbessou (1741-1774). The sons of the King who reached 10 years of age could not continue to live in the palace with the women. They left by this entrance to taught and educated [sic] at Vinhondji. Just as the son and heir, the Vidaxo, left by the same door to go to Ife in Nigeria, which is the country of origin of the Fa. That is where they instruct the sons and heirs in the domain of the Fa, in reading, in the Yoruba language, musical instruments and also patience.

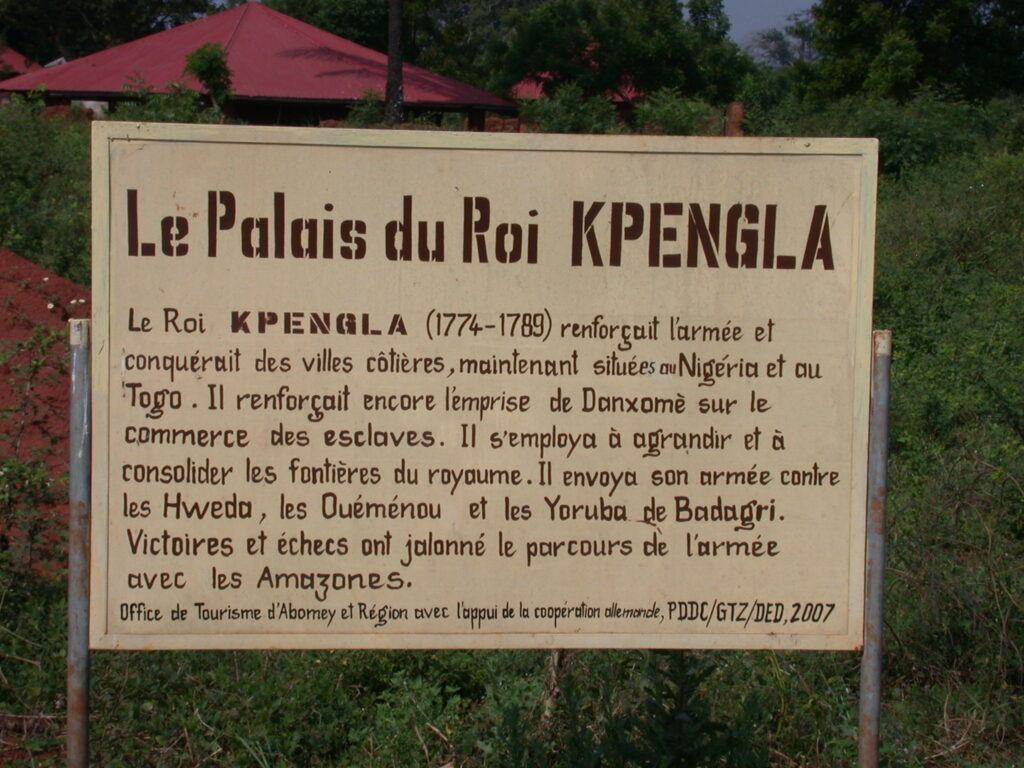

I translated into English the French sign describing the palace of King Kpengla:

The Palace of King Kpengla

King Kpengla (1774-1789) reinforced the army and conquered coastal cities, now situated in Nigeria and Togo. He still reinforced the Danxomè’s influence on the slave trade. He focused on expanding and consolidating the frontiers of the kingdom. He sent his army against the Hweda, the Ouemenou, and the Yoruba of Badagri. Victories and defeats charted the course of the army with the Amazons.

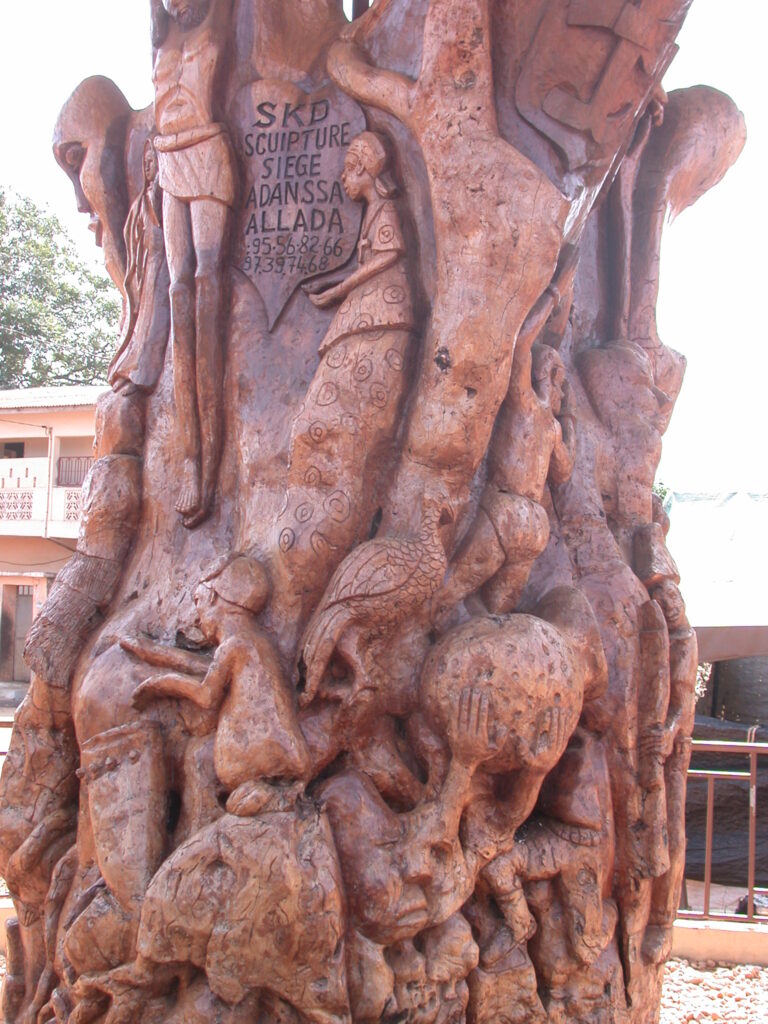

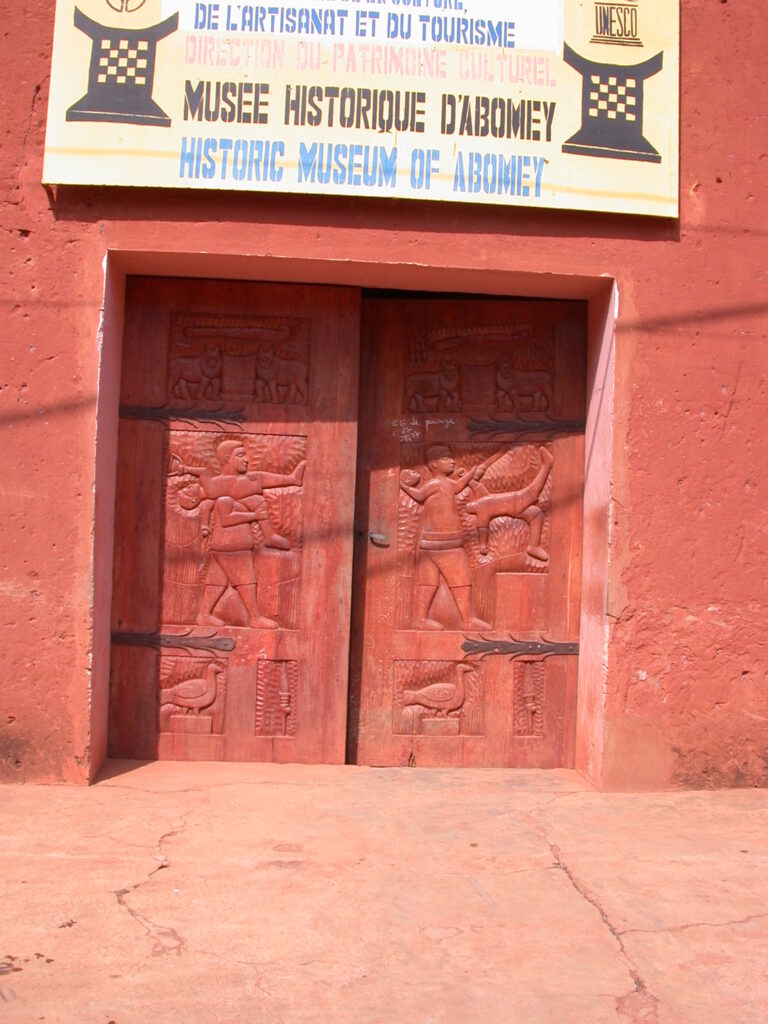

After wandering around all of these ruins, I arrived at the Musée Historique d’Abomey, where I spent a good chunk of cash on the admission and camera fee. The Musée Historique d’Abomey is located in the main complex of palaces with a large old tree in front.

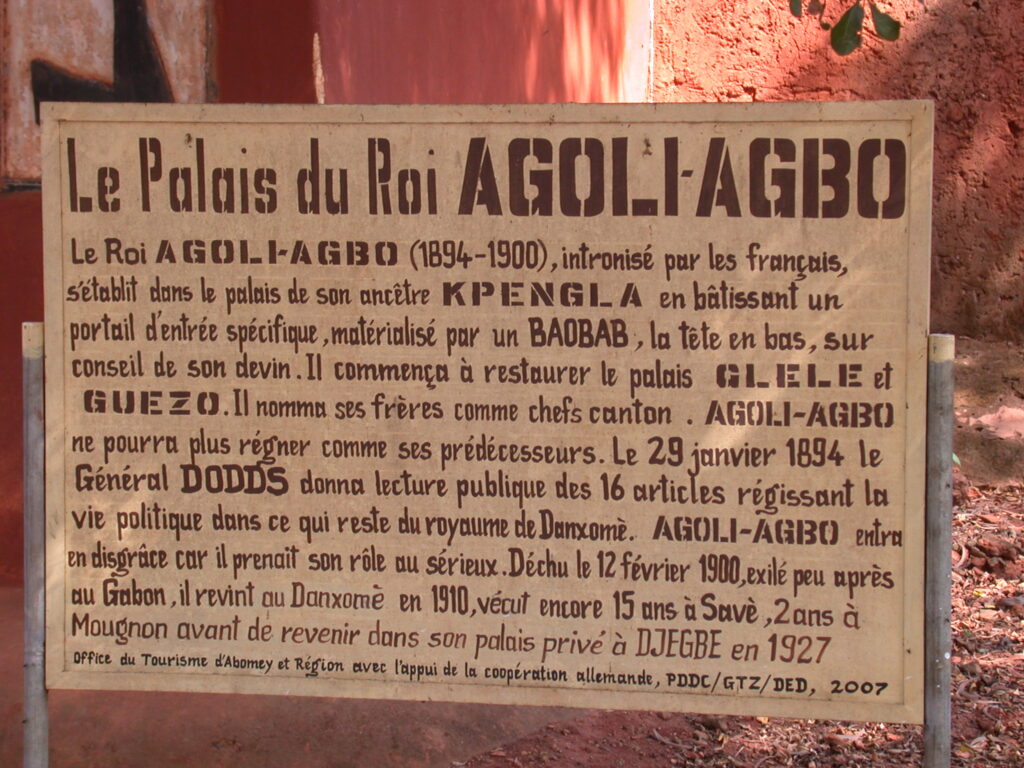

Here is my English translation of the French sign describing the palace of King Agoli-Agbo:

The Palace of King Agoli-Agbo

King Agoli-Agbo (1894-1900), enthroned by the French, established himself in the palace of his ancestor Kpengla by building a specific entry gate, materialized by a baobab tree, upside down, on the advice of his soothsayer. He started to restore the Glele and Guezo palace [sic]. He named his brothers as canton chiefs. Agoli-Agbo couldn’t reign like his predecessors anymore. On January 29, 1894, General Dodds read to the public 16 articles governing political life in what was left of the Danxomè kingdom. Agoli-Agbo went into disgrace because he took his role seriously. Deposed on February 12, 1900, exiled a bit later to Gabon, he returned to Danxomè in 1910, lived 15 more years at Savè, 2 years at Mougnon before returning to his private palace at Djegbe in 1927.

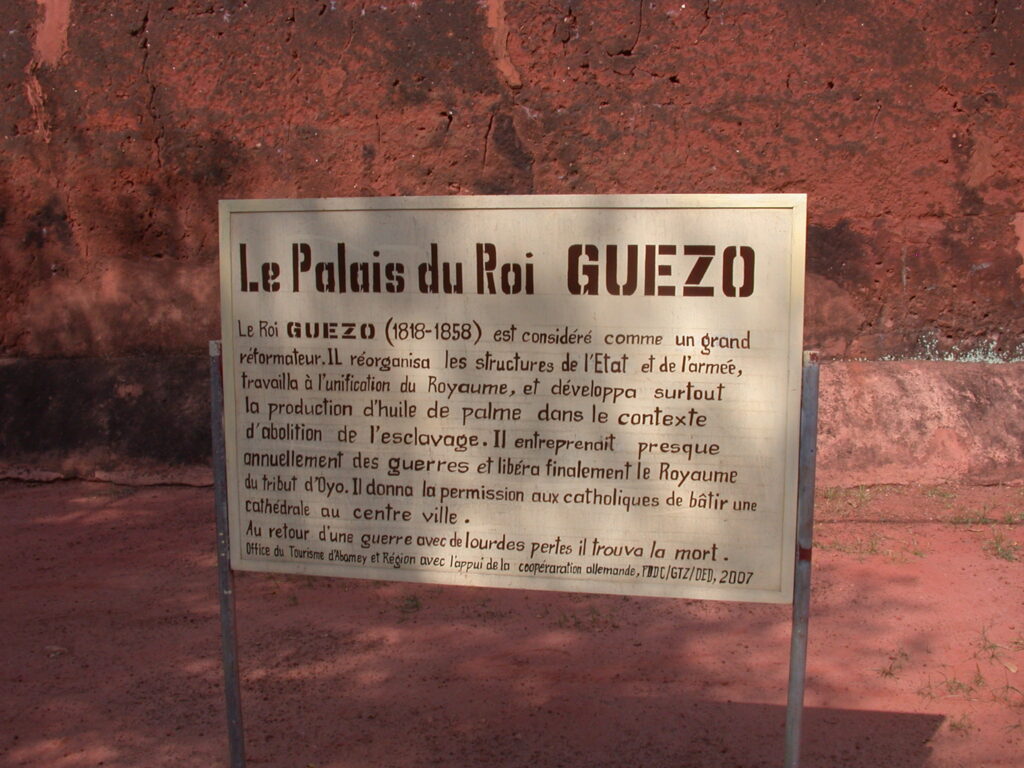

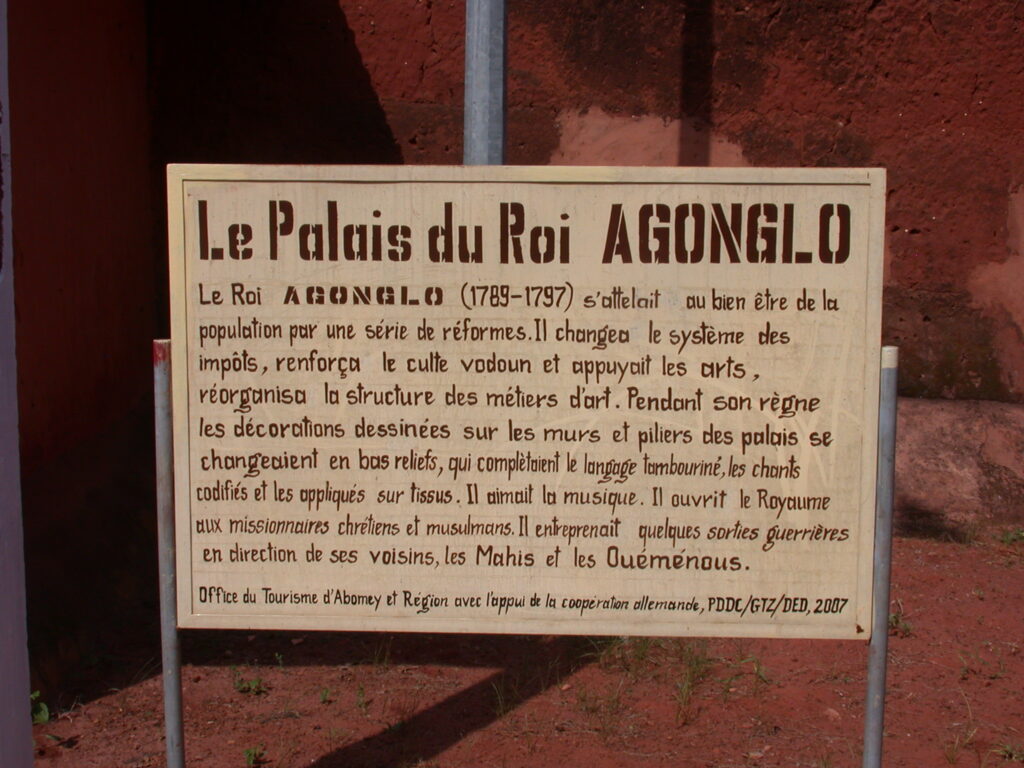

I read and photographed the signs for the palaces in the complex before entering the complex, since photography was not generally permitted inside. For each sign, my translation of the French sign precedes the photograph of the sign.

Ghezo Singbo

Two-Story House of Ghezo

This installation houses a Honnuwa identical to the others. This Honnuwa was transformed in Singbo (two stories) with the assistance of his friend Chacha de Souza.

The Palace of King Guezo

King Guezo (1818-1858) is considered a great reformer. He reorganized the structures of the State and the army, worked to unify the Kingdom and developed the production of palm oil in the context of the abolition of slavery. He undertook almost annual wars and freed finally the Kingdom from tribute to Oyo. He gave Catholics permission to build a cathedral downtown.

On the way back from a war with heavy losses, he found death.

Here is my translation of the sign for King Agonglo’s palace:

The Palace of King Agonglo

King Agonglo (1789-1797) saddled himself with the well-being of the population for a series of reforms. He changed the system of taxation, reinforced the voodoo (vodun) cult, and supported the arts, reorganizing the art trades. During his reign, the designed decorations on the walls and pillars of the palace changed into bas reliefs, which completed the drummed language, codified chants and applied them to cloth. He loved music. He opened the Kingdom to Christian and Muslim missionaries. He undertook some war expeditions in the direction of his neighbors, the Mahi and the Ouemenous.

Some people hid away to prepare for rituals in alcoves of the palace.

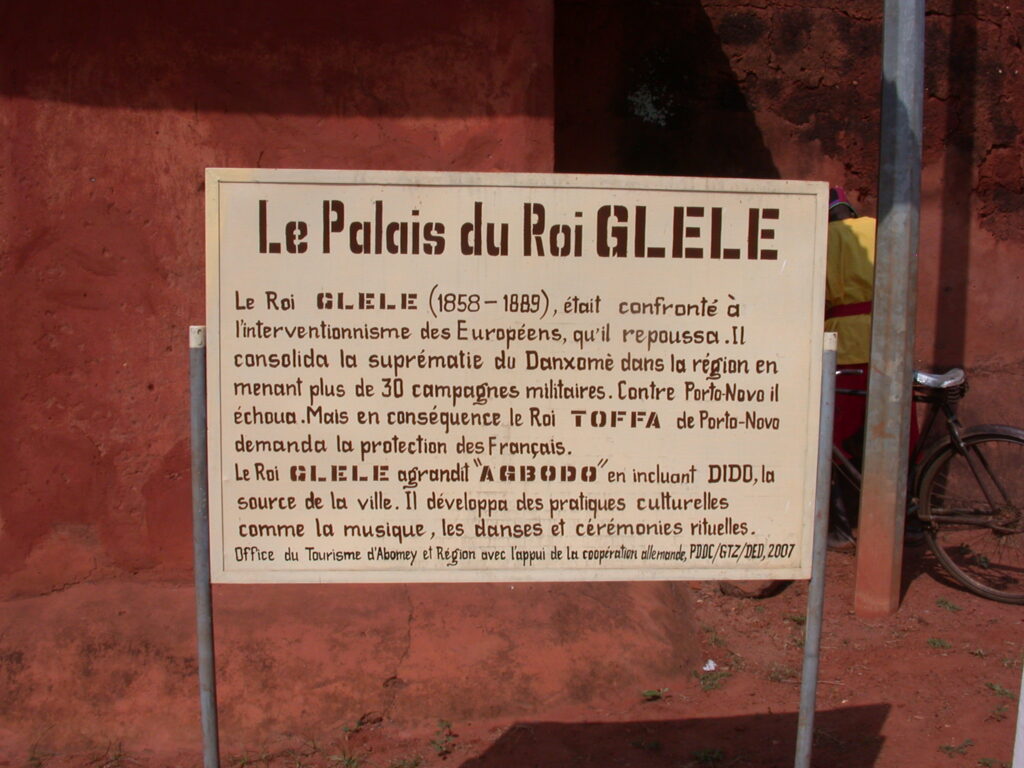

Here is my translation of the sign for King Glele’s palace:

The Palace of King Glele

King Glele (1858-1889) was confronted by the interventionism of the Europeans, which he repulsed. He consolidated the supremacy of Danxomè in the region by carrying out more than 30 military campaigns. Against Porto Novo he lost. But as a result King Toffa of Porto Novo asked for the protection of the French.

King Glele enlarged “Agbodo” by including Dido, the spring of the city. He developed cultural practices like music, dance, and ceremonial rituals.

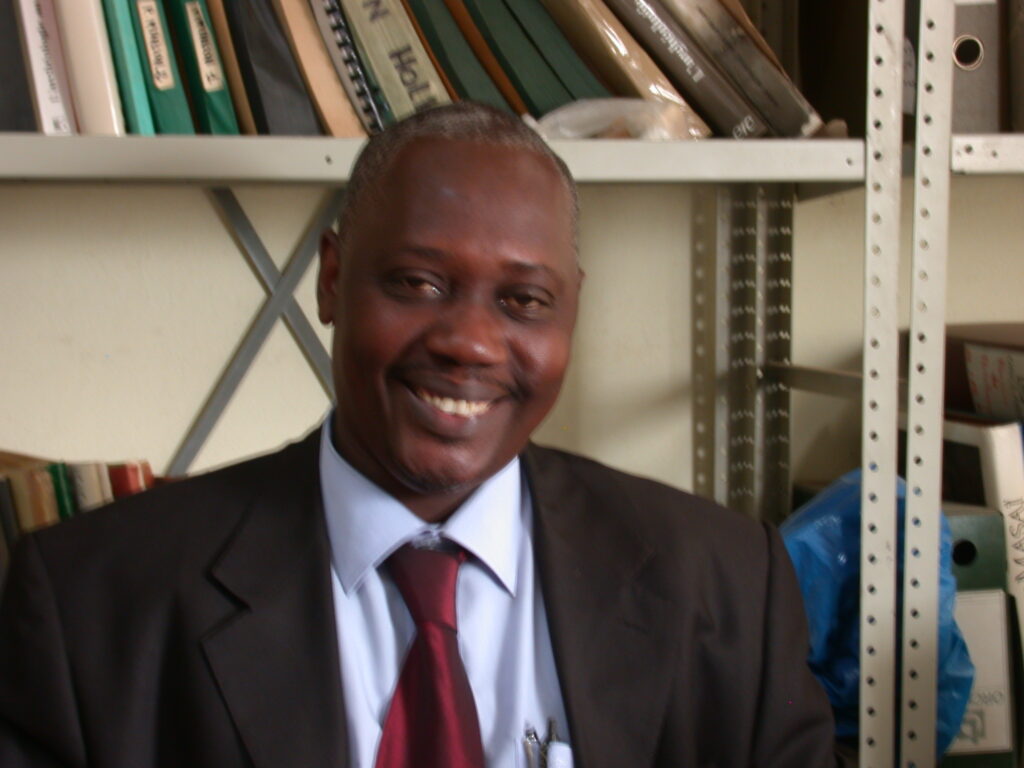

After I entered the museum complex, the guide was happy to see me, as he was starting to guide a group of Finnish women visiting from where they were staying in Porto Novo. They spoke English, but not French. As his primary guide language was French, he was happy to have my assistance with interpretation. I enjoyed helping the group out.

The palace is amazing… apparently the kings used to order warriors out to battle — on departure, they would commit to a number of human heads they intended to bring back. If they succeeded according to their commitment, the king rewarded them with advancement. If they returned with fewer than the promised number, their own head was required to fulfill the balance. So, unsuccessful warriors were unlikely to return at all.

The fiercest warriors were the Abomey Amazons, women specially trained for military service. They were not only the best warriors, but also apparently the best at tracking and recapturing escaped slaves brought in from other districts for use in Abomey or sale elsewhere.

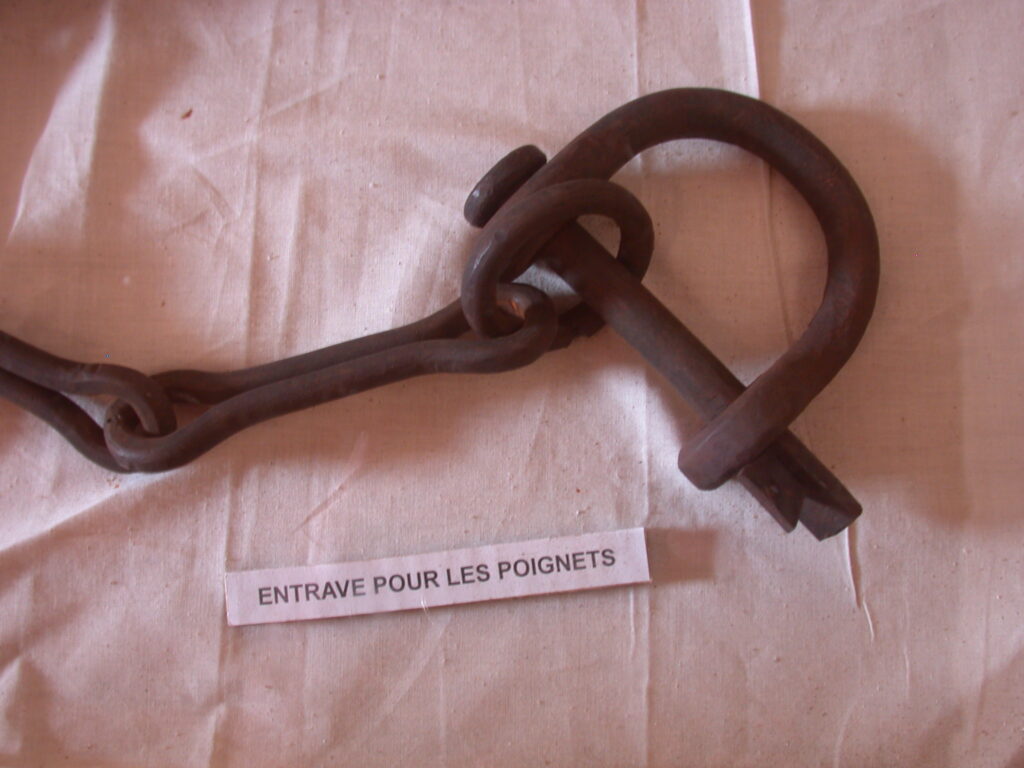

The king bought cannons, each one in exchange for 15 male slaves or 21 females slaves.

There is a temple for offerings to the king after he died that has a tunnel communicating to a more private part of the palace compound. The queen mother was also buried there, although she was usually not the mother of the king or his wife.

As we wandered through the palace grounds, large numbers of celebrants took part in the Danxome Festival festivities that started that day. This included costumed men riding decorated horses, all manner of traditional dancing, some children dancing with Mickey Mouse masks, and a large presentation area where various officials and VIPs sat.

I left the palace after goodbyes to the Finns and the guide, then ran into a bunch of drummers playing the kind of drum used as talking drums. They urged me to dance while they drummed, so I did. I tried to get them to “talk” with the drum, but they didn’t or couldn’t, so I went on my way after giving them a little baksheesh.

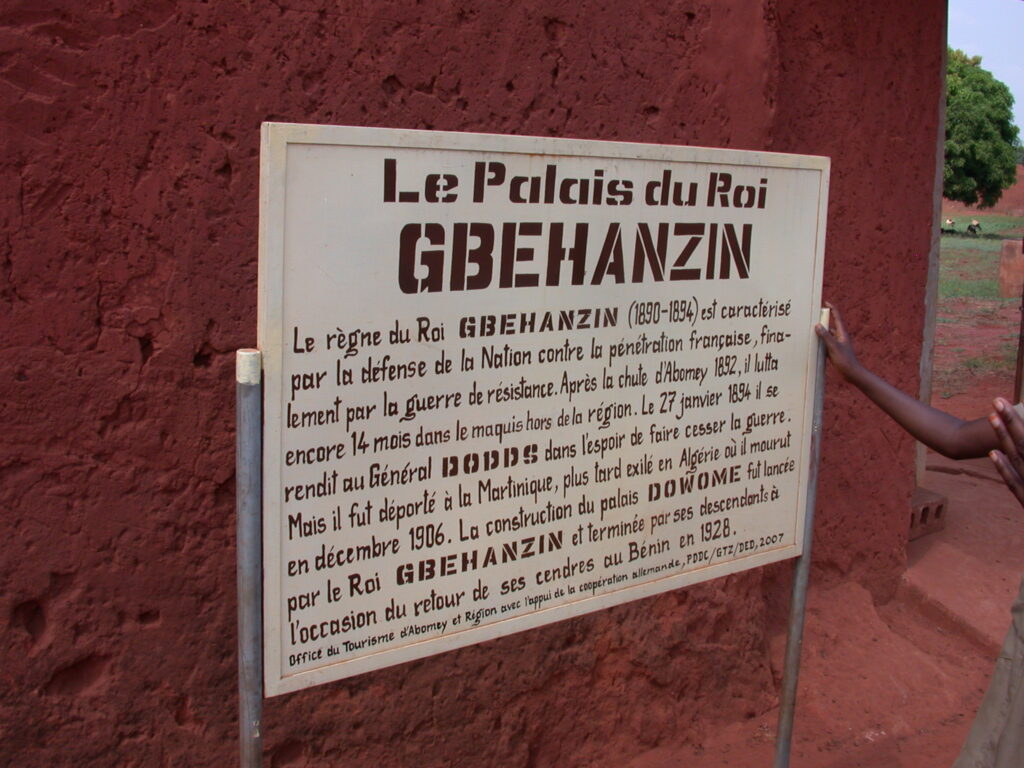

I came across the palace of King Gbehanzin next and translated into English the French sign there as follows:

The Palace of King Gbehanzin

The reign of King Gbehanzin (1890-1894) was characterized by the defense of the Nation against French penetration, finally by a war of resistance. After the fall of Abomey in 1892, he fought 14 months more in the bush out of the region. January 27, 1894, he went to General Dodds in the hope of ending the war. But he was deported to Martinique, later exiled in Algeria where he died in December 1906. The construction of the Dowome palace was started by King Gbehanzin and finished by his descendants on the occasion of the return of his ashes to Benin in 1928.

I passed a busy market en route between the multitude of palaces and temples.

At one temple, I looked around to see if anyone was taking care of it, then not seeing anyone, I took some pictures, after which a fellow came up to me aggressively demanding what I was doing and telling me I can’t just go around taking pictures of whatever I like. The resolution of the matter ended up being my negotiation with the chief’s son to erase a few pictures on the camera after which I had to show him they were really erased.

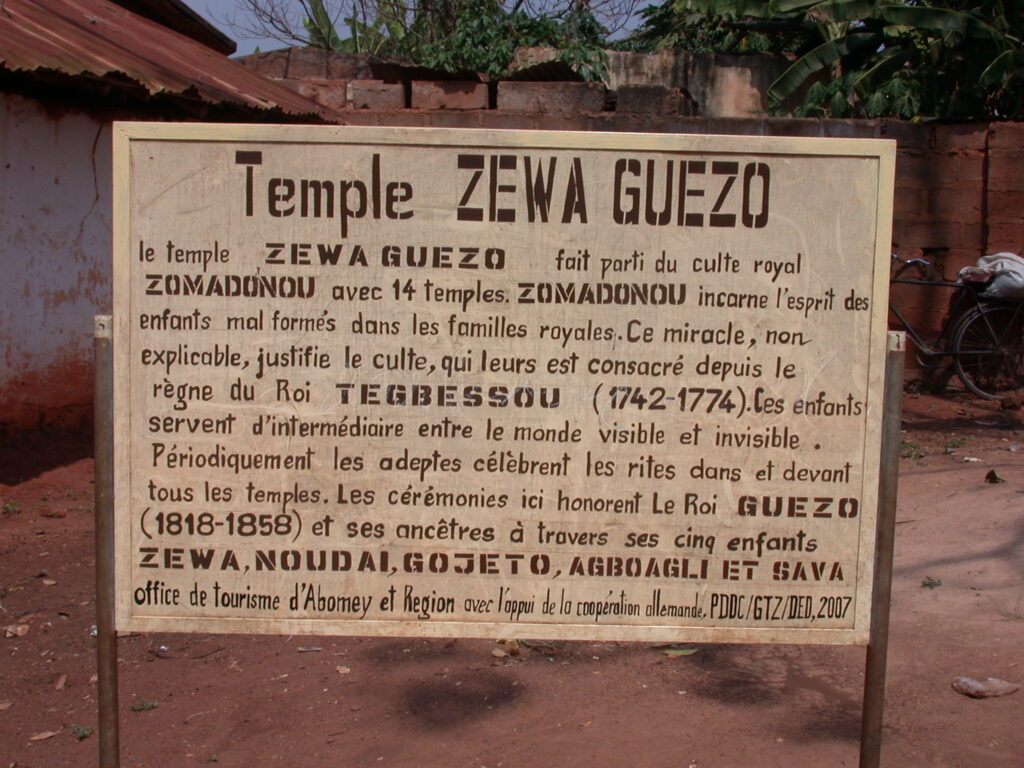

Here is my translation of the French sign for the Zewa Guezo temple:

Zewa Guezo Temple

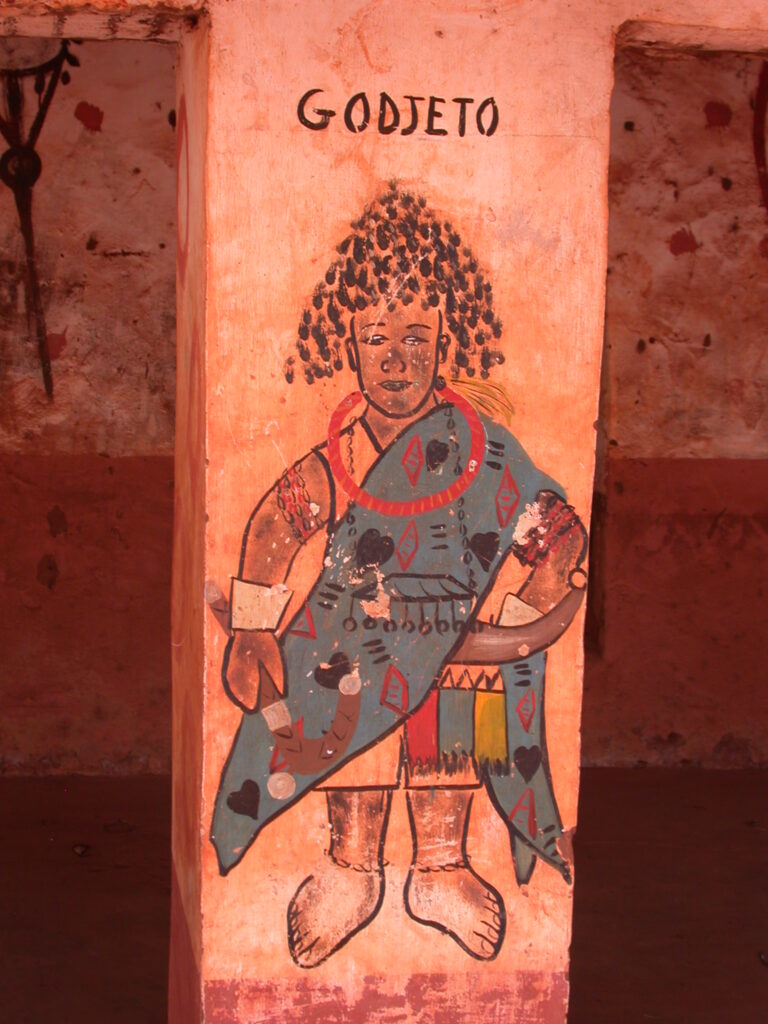

The Zewa Guezo temple is part of the Zomadonou royal cult with 14 temples. Zomadonou incarnates the spirit of malformed children in the royal family. This inexplicable miracle justifies the consecration of the cult during the reign of King Tegbessou (1742-1774). These children serve as intermediaries between the visible and invisible world. Periodically the adepts celebrate rites in and in front of all the temples. The ceremonies here honor King Guezo (1818-1858) and his ancestors through his five children Zewa, Noudai, Gojeto, Agboagli, and Sava.

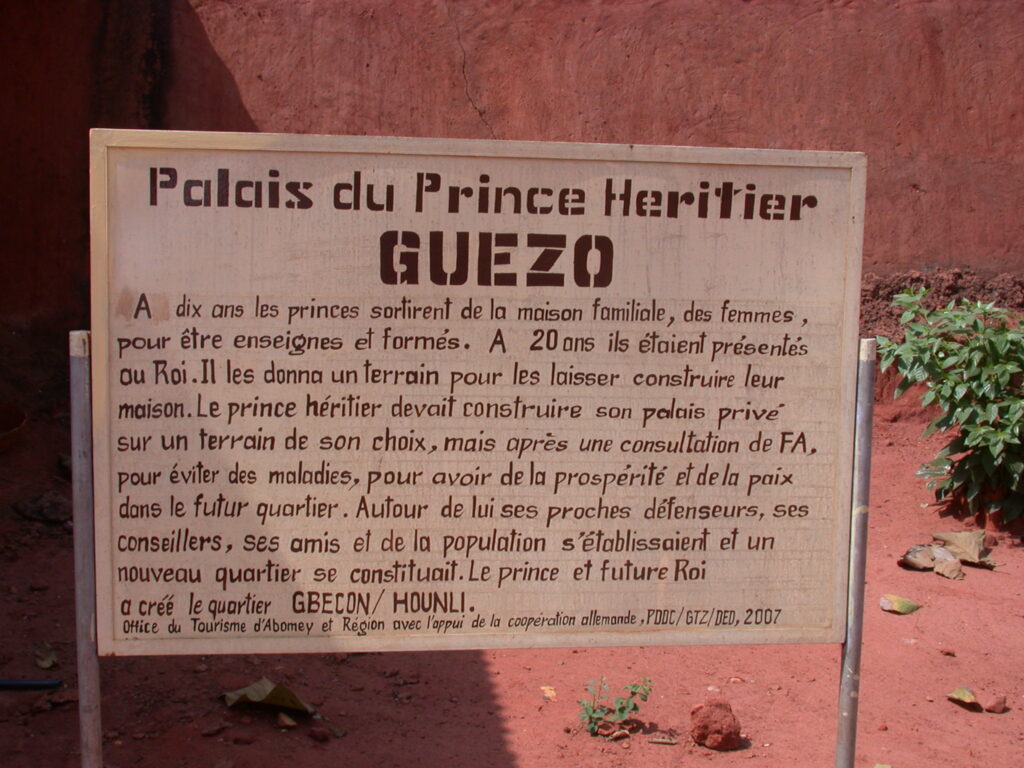

Here is my translation of the French sign for the palace of the Crown Prince Guezo:

Palace of the Crown Prince Guezo

At ten years of age, the princes leave the family house and the women to be taught and instructed. At 20 years of age, they are presented to the King. He gives them land to let them construct a house. The crown prince must construct his private palace on a plot of his choice, but after a Fa consultation, to prevent illnesses, to have prosperity and peace in the future neighborhood. Around him his close defenders, his counselors, his friends, and the populace established themselves and constituted a new neighborhood. The prince and future King created the Gbecon/Hounli neighborhood.

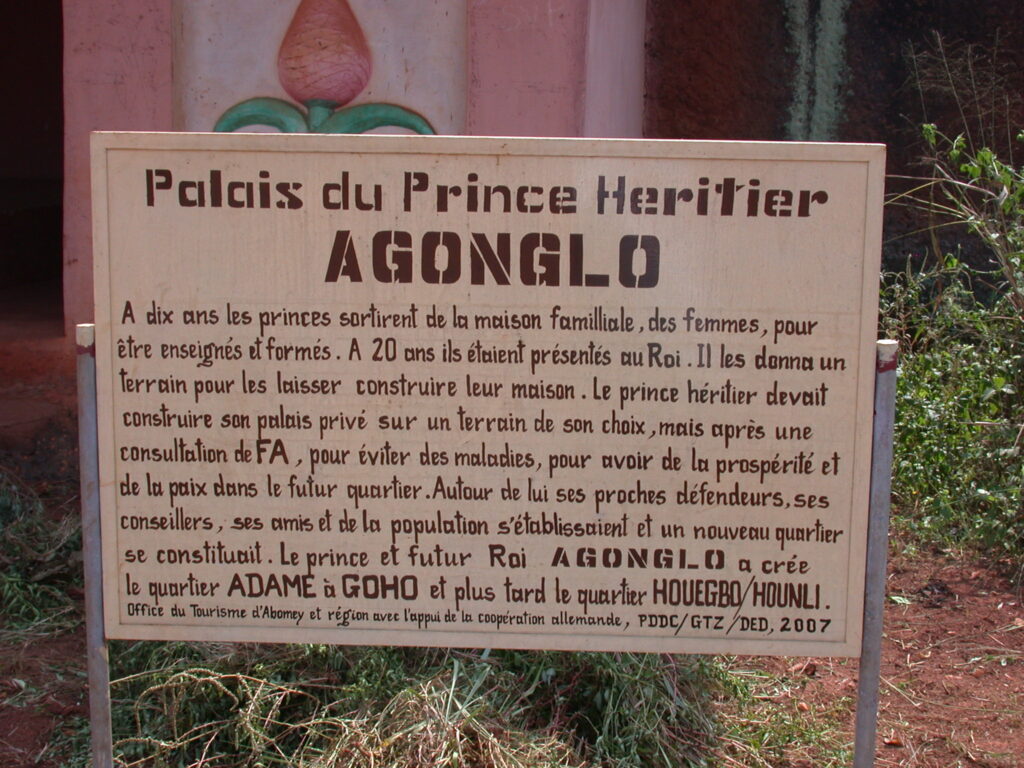

Here is my translation of the French sign for the palace of the Crown Prince Agonglo:

Palace of the Crown Prince Agonglo

At ten years of age, the princes leave the family house and the women to be taught and instructed. At 20 years of age, they are presented to the King. He gives them land to let them construct a house. The crown prince must construct his private palace on a plot of his choice, but after a Fa consultation, to prevent illnesses, to have prosperity and peace in the future neighborhood. Around him his close defenders, his counselors, his friends, and the populace established themselves and constituted a new neighborhood. The prince and future King Agonglo created the Adame neighborhood at Goho and later the Houegbo/Hounli neighborhood.

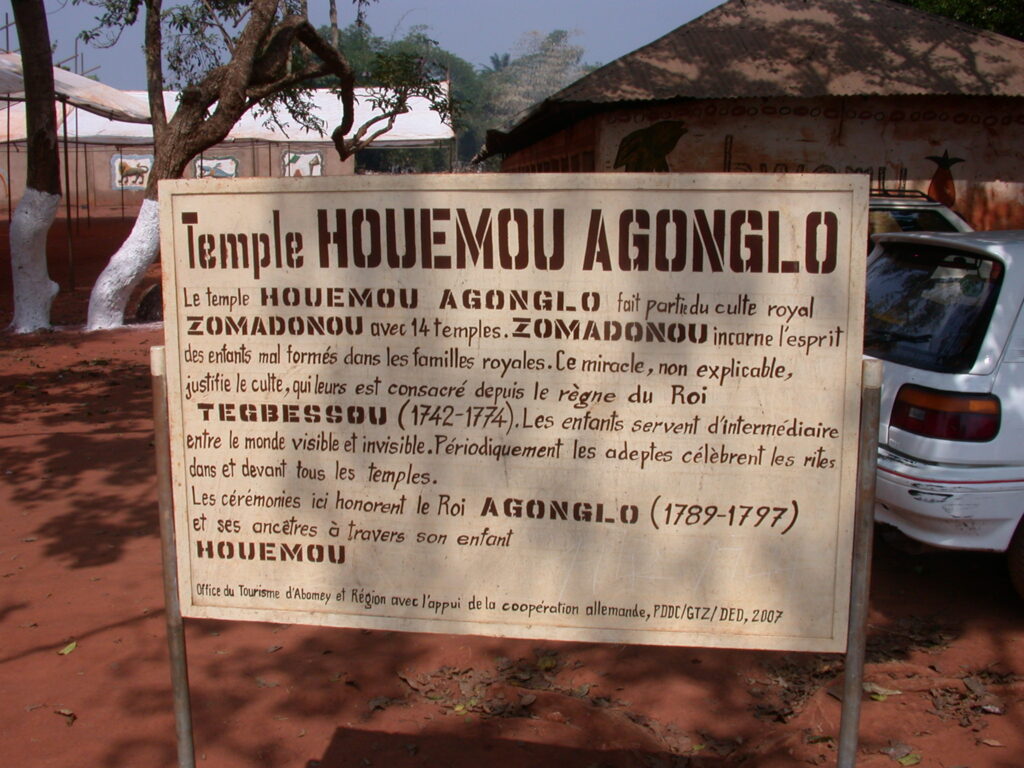

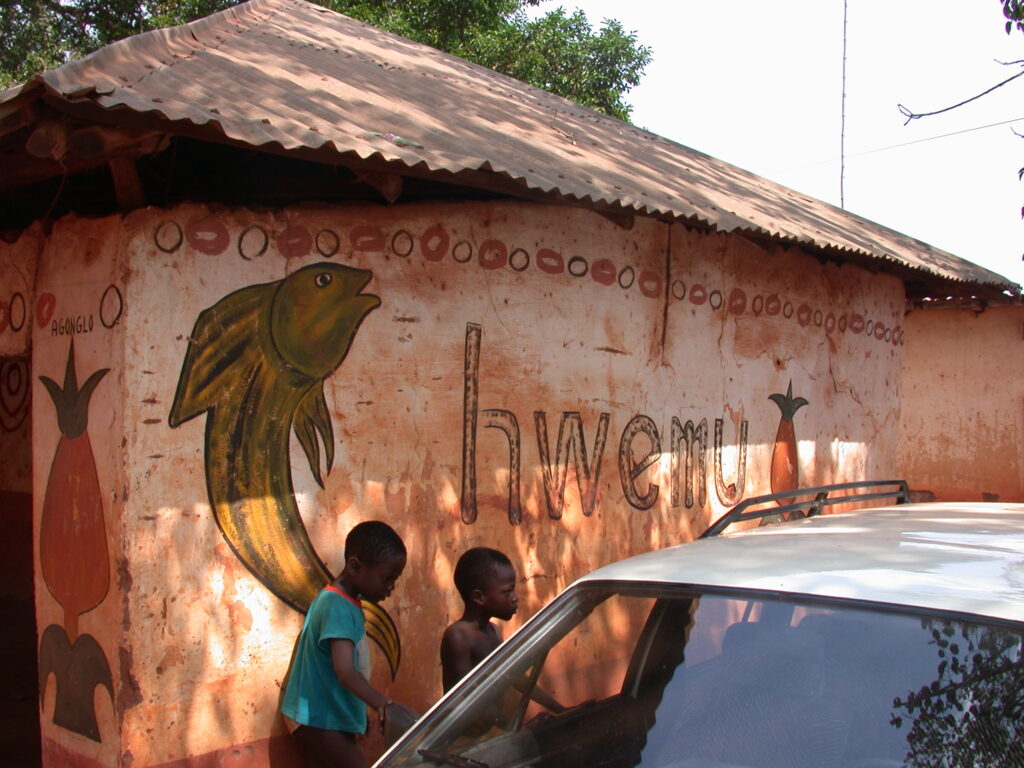

I came across the Houemou Agonglo Temple and its sign which read as follows in English translation of the French original:

Houemou Agonglo Temple

The Houemou Agonglo temple is part of the royal cult of Zomadonou with 14 temples. Zomadonou incarnates the spirit of malformed children in the royal family. This inexplicable miracle justifies the consecration of the cult during the reign of King Tegbessou (1742-1774). These children serve as intermediaries between the visible and invisible world. Periodically the adepts celebrate rites in and in front of all the temples. The ceremonies here honor King Agonglo (1789-1797) and his ancestors through his child Hoeumou.

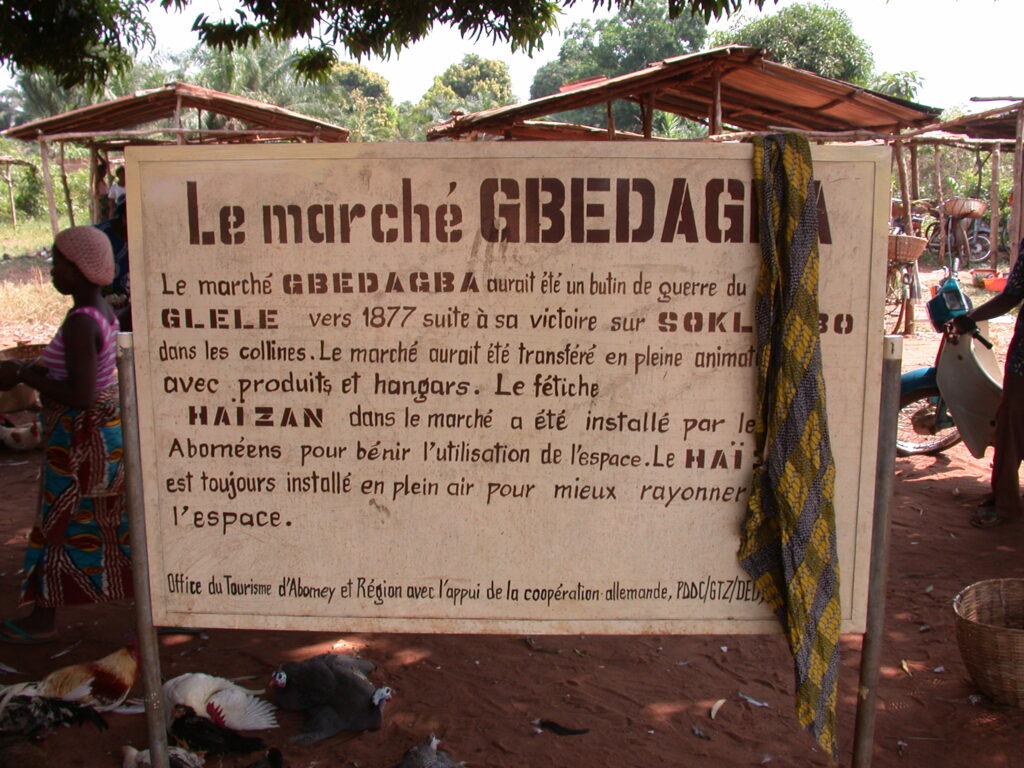

After all those palaces and temples, I worked up a real thirst, so I had a drink at a little pub just past a market with goats and chickens and a special fetish in the middle of the market. I translated the French sign there as follows:

The Gbedagba Market

The Gbedagba market was a spoil of war of King Glele around 1877 following his victory over Sokl???bo [covered by cloth] in the hills. The market was transferred in full working order with products and booths. The Haïzan fetish in the market was installed by the Abomeans to bless the use of the space. The Haïzan is always installed in the open air to better radiate through the space.

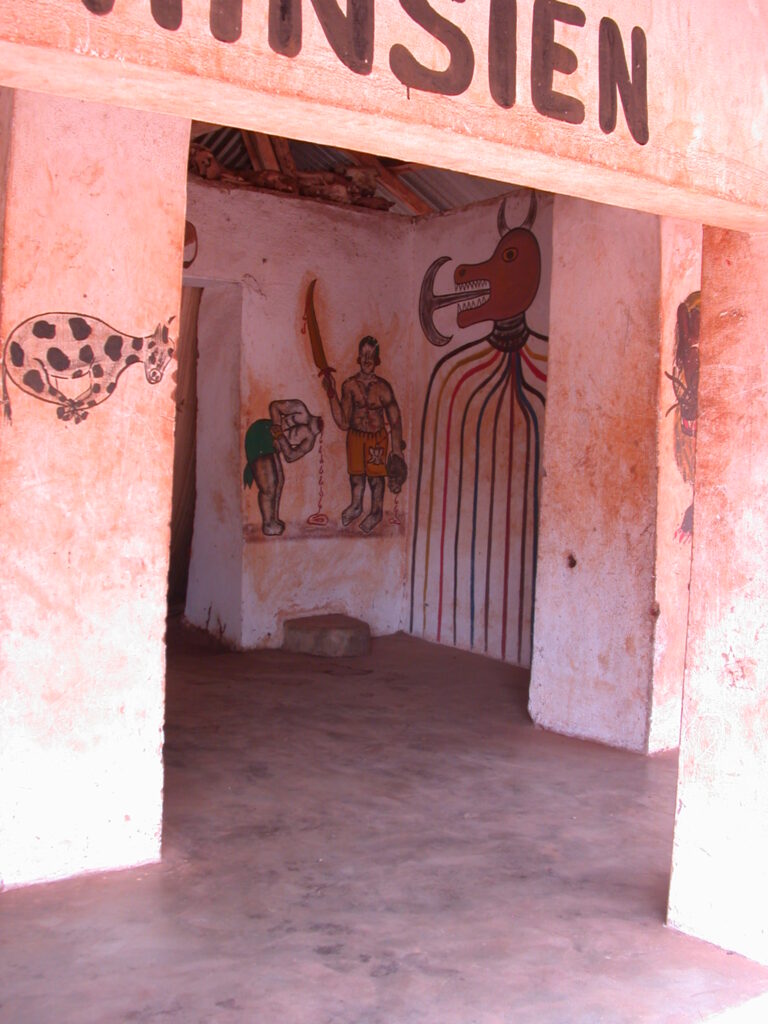

I tried to find the twin fetish and the fertility fetish, which had apparently been vandalized by a female tourist who sought to take the protruding part of the fetish with her. After first getting permission from a woman at the compound next to the Sémassou Temple, I then had to negotiate again with a man who said the woman didn’t have the right to do what she had done, then let a disabled boy on a bike show me the twin fetish and what may have been the damaged fertility fetish, of which I took pictures. I now realize how appropriate it was for a disabled boy to be showing me around the site.

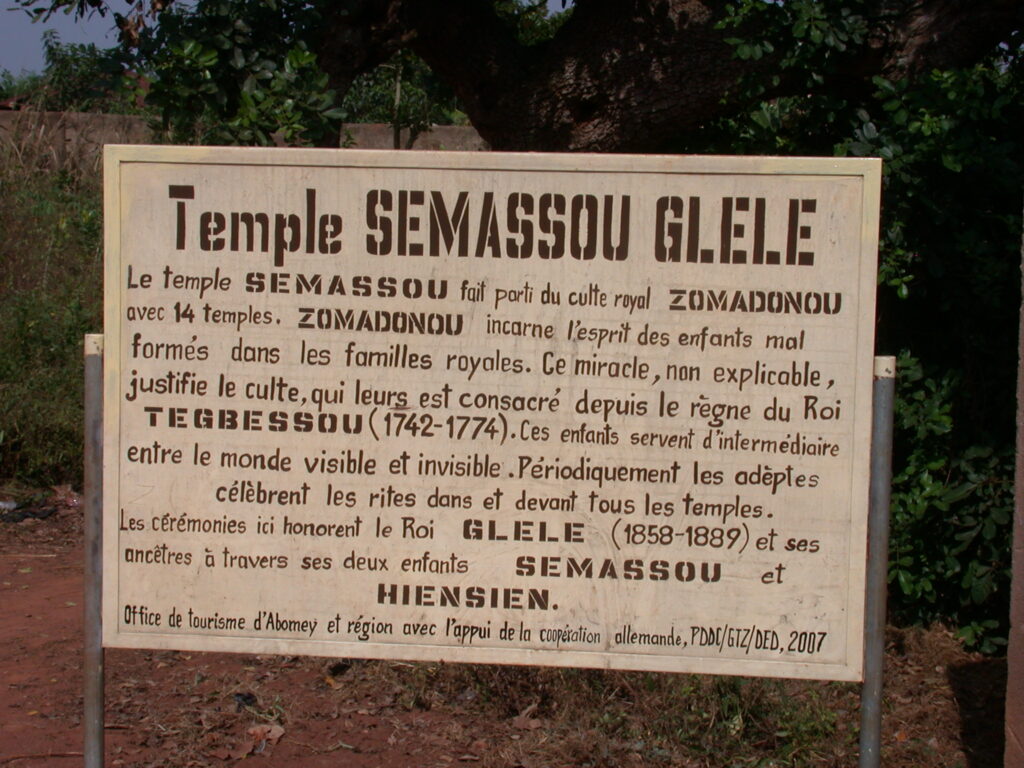

I start with my translation of the French sign at the Semassou Glele temple:

Semassou Glele Temple

The Semassou Glele Temple is part of the royal cult of Zomadonou with 14 temples. Zomadonou incarnates the spirit of malformed children in the royal family. This inexplicable miracle justifies the consecration of the cult during the reign of King Tegbessou (1742-1774). These children serve as intermediaries between the visible and invisible world. Periodically the adepts celebrate rites in and in front of all the temples. The ceremonies here honor King Glele (1858-1889) and his ancestors through his two children Semassou and Hiensien.

Here is a picture of the fertility fetish as it was when I saw it:

Here is a picture taken by a photographer named Mark Wilkinson apparently before the removal of the phallus from the fertility fetish:

Here is the twin fetish as I saw it:

They wouldn’t budge on the python temple though, neither to look inside it or to take pictures of it. In the end, a bit more baksheesh brought the man around.

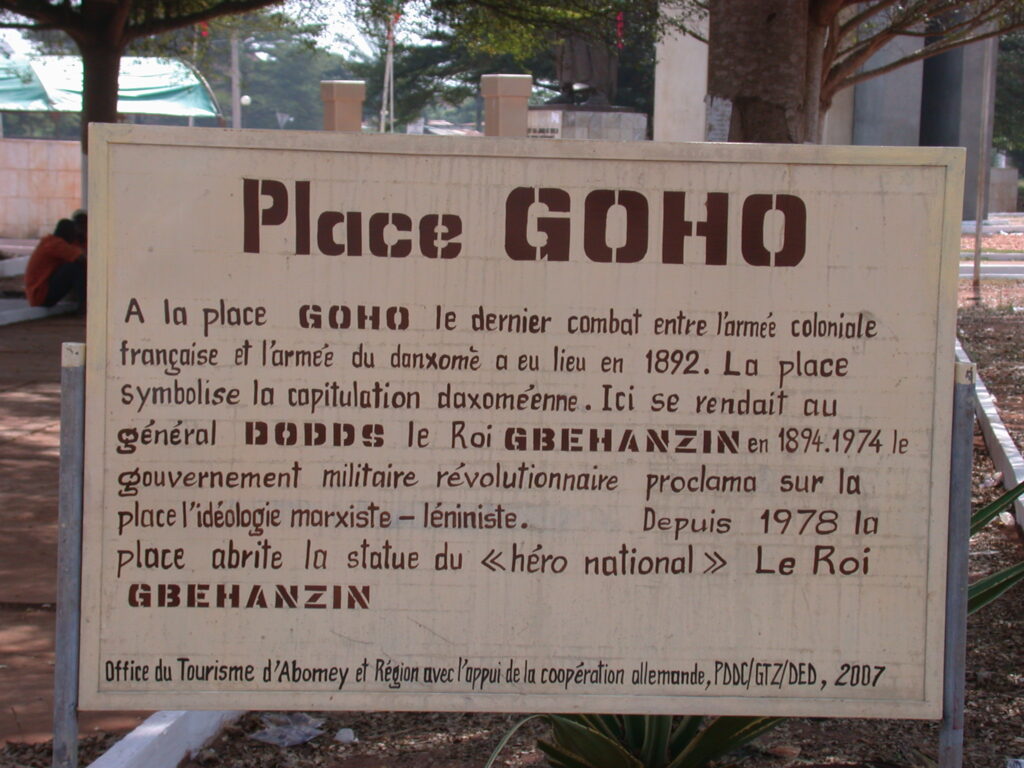

Afterwards, he even stopped a guy who was driving by to give me a ride back to the Place Goho roundabout near the hotel where I was staying. I translated the French sign there as follows:

Goho Place

The final combat between the French colonial army and the Dahomean army took place at Goho place in 1892. The place symbolizes Dahomey’s capitulation. Here King Gbehanzin surrendered to General Dodds in 1894. In 1974, the revolutionary military government proclaimed the Marxist-Leninist ideology in the place. Since 1978, the place has hosted the statue of the “national hero” King Gbehanzin.

I didn’t arrive back at the hotel until well after checkout time, so I decided to spend another night there before heading on to Cotonou to pick up my visa. On the television was the strange spectacle of a program called “Window on Islam” with pilgrims on the the hajj circling the Ka’aba in Mecca while French-language advertisements ran across the bottom of the screen.

At breakfast before I left, I snapped a pic of the cool painted optical illusion decoration on a pillar of the porch in front of the hotel that looks alternately like a bottle or two wine glasses.