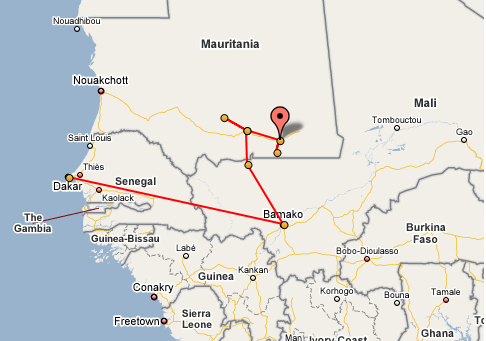

The truck guys from Koumbi Salah, Baba and Sidi, were off having tea while I spoke for awhile with Hassan, then he sent me off with them after they had already picked up some passengers along the way. Baba got the owner guy to translate that he too wanted a cadeau. I asked if I had already paid for the ride and they agreed I had. The first third of the ride to Timbedra, Sidi the navigator wanted to get in on the act and kept nagging me for a gift. I kept telling him to talk with Hassan if he had any problem. But he just wouldn’t stop after dozens of times, so I just put my fingers in my ears and sulked for awhile. Only that seemed to work. I felt actually quite hurt because I had through we were becoming friends, or at least buddies. I sat without speaking and pondered the situation — the needs some people have or feel they have, the stereotype of the rich foreigner, what it means to give, to ask, and to demand, and how to set limits to make my voyage even possible. I nearly cried.

Finally, we arrived in Timbedra. I gave Baba Ahmed, the driver, and Sidi Mohammed, the navigator, each a small packet of tea as a gift, then we said our goodbyes. The meditation on this experience brought me to a place where I could thank the rip-off artist who brought me to Aoudaghost for helping me to learn a lesson.

In Timbedra, I hitched a quick ride to the garage for Nema. I waited awhile for a vehicle that didn’t look like it was leaving anytime soon, since they drive wanted a total of nine passengers. After two other passengers had paid, and I had wisely withheld paying, another driver offered to take me for 3000 ougiya instead of the first car’s price of 1000 ougiya, but with the advantage of having no other passengers, and more importantly of leaving right away. We did actually leave fairly soon thereafter, following an argument between all the drivers at the garage and a threat to call the police. Of course, the driver I went with packed the back seat with passengers, but at least didn’t try to push any more into the front seat with me. We got underway, and the driver, a Malian from Bamako who already had four kids by two Mauritanian wives, grilled me about how to get to America to make lots of money. I explained the usual four ways I know of and discussed at length with him why it would be difficult for him to marry an American woman.

We arrived at Nema and I dragged my bags through the sandy market streets to the “permanent garage” for Oualata. For some reason, the driver wouldn’t sell me the more expensive seat in the front of the vehicle. While sitting on the sidewalk waiting, I say “es salaam aleykum” to virtually everyone who passes by and chat with whomever seems interested or interesting. Most of the conversations are in halting French or minimalist Hassinaya/Arabic about where I am from, where I am going, and what is my name. I tried to telephone the Peace Corps volunteers here that the Ayoun volunteers had mentioned, but it was impossible to find a phone, and I didn’t have a Mauritanian “puce” or SIM card for my travel cellphone.

Written on November 18, 2007, Hotel de l’Amitié, Oualata, Mauritania

The truck ride from Nema to Oualata was the most trying ride I’ve ever had, and I’ve been in some pretty horrible rides. I tried to reserve a place in the cab, but the truck owner said he wouldn’t be able to tell me if that was possible until 3pm. I had arrived at the “garage” around 11:30am. When some other passengers came along and he no doubt sold the cab seats to them, he glanced at me smiling. Somehow I knew he hated my guts, although I had never done anything to him. The problem continued with the owner of the truck not ensuring the truck bed was clean. Some animal, probably a goat, had pissed on the fiber netting and the driver hadn’t washed the netting or the truck bed since. The owner managed to pack my bag where the pissy portion of the netting was. When I protested, he face broke into a wide smile. I sarcastically laughed back and him and he back at me. I handed him 1000 ougiya and told him that’s all the seat he gave me was worth. He looked worried for a second, then greedily demanded the other 1000 ougiya for the price of the ride. My plan, after being relegated to the truck bed, was to position my bag so I could rest my back in relative comfort against it while riding. That plan was foiled because I couldn’t stand to sit down in the pissy netting. I was already immersed in the stink of it within five minutes after getting on the truck. The terrain was at times comparable to some of the worst bumpy and sandy desert roads I encountered in out-back Sudan. But what made the ride absolutely miserable was the way the truck owner packed myself and the other passengers in the bed of the truck along with a continually protesting goat and all our baggage. While some passengers admittedly rode in relative comfort up front, that is, squished in the seats of the large cab of the truck, the rest of us squatted, perched, and squirmed as the truck bumped and swerved for hours. At the last moment on the way out of town, I saw a toubab, a white woman, wandering the streets of Nema who I would coincidentally meet again later on. The route to Oualata seemed never to end, winding and twisting, at times backtracking for the correct route. Once we spotted a town and my spirits lifted only to have my hopes crushed by finding out it was another town and we still had a long ride to come. Every cloud has its silver lining and this trip was no exception. The sunset was exquisite. When we stopped for evening prayers, one fellow taught me how to put on a turban properly and we reshuffled ourselves in the truck bed. For about twenty minutes, I was actually comfortable — that is, until we picked up another passenger along the way, a handsome young fellow with deep brown doe eyes, startled by my appearance, but sitting basically in my lap with my legs spread wide and squished down below everyone else’s body parts. By the time we arrived in Oualata, I worried my legs and neck had received serious damage. After proceeding under a crazy welcoming town arch, the truck stopped at a police outpost. I tried explaining the name of the hotel where I wanted to go, but no one understood until I tried saying the name of the hotel’s owner and suddenly they figured out where I wanted to go. The “streets” were dark except for electric street lamps located at seemingly random spots around the town. The police officer took my passport to a little mud-brick building where he slept, ate, and conducted his duties. He insisted on copying my name and passport number, although he couldn’t spell in English or French. Eventually, he wrote my name in Arabic, even though I offered to write it several times myself for him. Meanwhile the passengers on the truck were getting restless and, preparing to abandon me there, the driver brought my bags to me. I groaned and the police officer said it was OK to leave, so I started dragging my bags back to the truck just as it was preparing to go. I yelled “Merde” (“Shit”) loudly. The truck waited for me to get my bags back on board, then started to leave without me having a chance to crawl back on so I had to thwack the side of the truck until the driver stopped, then clambered on board completely and utterly exhausted and nearly hysterical with stress. The driver dropped everyone else but me off first, and I even helped him unload several heavy sacks of grains and vegetables. Finally, the truck arrived at the hotel and Mr. Ahmed Moulay came out front to greet me. My final moment of high stress ended when he answered that there was indeed room at the inn, so I grabbed my large bag and he my small one, waved a quick goodbye to the driver, and entered the hotel compound.